Some of my dearest early memories involve water. My dad would tie a rope on my sister’s and my life jackets as we doggie-paddled in the Oyster River under the old wooden bridge, then he’d reel us in like prize steelhead when we tired.

Then there was swim club, rowing the dinghy in Desolation Sound, and sea kayaking the Nuchatlitz. As a teenager, my sister even donned a fanny pack and whistle to work as a lifeguard at Courtenay’s outdoor pool.

Last year, I found out my grandma never learned to swim. This came as a shock. My strong-willed, commanding, loud, and robust grandma couldn’t swim? Why didn’t she ever complete this childhood rite of passage?

The answer made my stomach churn. When my grandma was growing up in Victoria, people of Chinese descent were not allowed to enter the city’s Crystal Pool. How had I not known this? And what else couldn’t Canadian-born Chinese people do in that era?

I grieved for her summers, void of the refreshing cool of rivers, lakes, or sea. Is that why she founded Victoria’s Chinese Drill Team—an indoor activity that took place far from water and, perhaps, in response to being similarly excluded from the city’s all-white Girls Drill Team?

The more I pondered these questions, the more I realized that outdoor recreation hasn’t always been guaranteed to all communities. The outdoors might have been an unsafe place for my grandma to learn to swim due to heightened tensions stemming from violent acts and government policies of the time. In 1907, the Asiatic Exclusion League, a group motivated by anti-Asian sentiment, instigated Vancouver’s first race riot, resulting in destruction in Chinatown and Japantown. My grandma was born in 1923, the year the Chinese head tax was replaced by the Chinese Exclusion Act barring Chinese people from immigrating to Canada (save for an exempt few). The message from the Canadian government was undeniably clear: my grandmother and her kin were not welcome. The ban from the public pool was the municipal government reinforcing the message: You do not belong.

Similar tensions might have existed for my late mother, too. Though she was the fourth generation in British Columbia, she used to recount stories of children yelling racial slurs and throwing rocks at her as she walked to school. If that type of violence occurred in broad daylight in an urban neighbourhood, I can only imagine what might happen in a dark wooded area. Yet, by high school, my mother had found a group of friends who mentored her in hiking and canoeing, something her family never did. She developed a passion for these activities, which she shared with us.

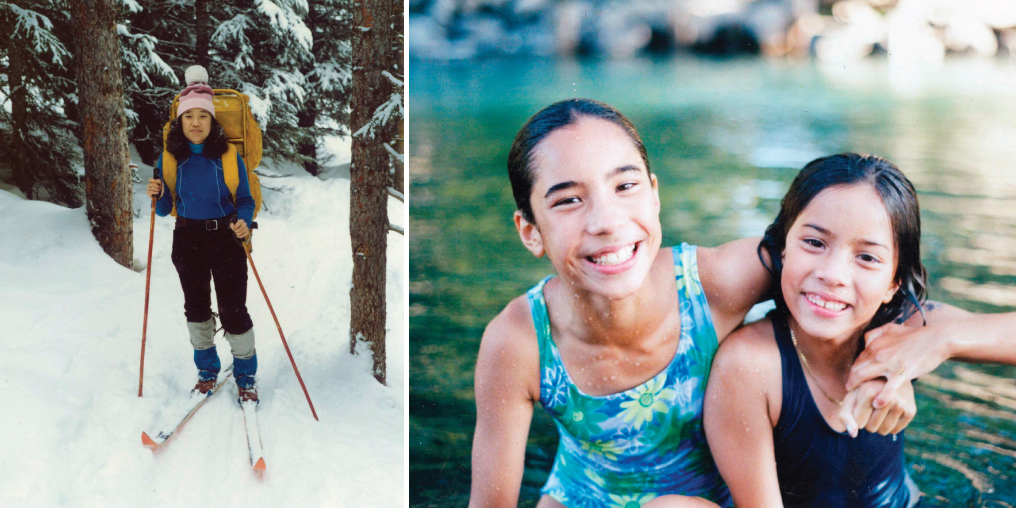

As a fifth-generation Chinese and Scottish/Ukrainian mixed-heritage child, I had few role models to look up to. The media portrayed the type of people who went outdoors, and they didn’t look like me. Yet the outdoors was how my family carved out quality time. Whether it was hiking to San Josef Bay or staying close to home for bonfires at Saratoga Beach, my family encouraged us to explore. In the winter, we skied loppets around Paradise Meadows with the Jackrabbits Nordic ski program. My sister and I were the only non-white kids. Maybe my mother wanted us to know all that was denied to her mother.

PHOTOS BY THE KEEN FAMILY

These early and immersive outdoor experiences instilled a fondness and reverence in me for wild spaces.

People are drawn to nature, and it’s no wonder: much recent research has sought to define the physical, mental, and emotional health benefits of being in nature.

Unsurprisingly, they are vast and varied—so much so that physicians in many Canadian provinces can now write “nature prescriptions” for patients that include a free annual pass to national parks. Studies show that to receive nature’s health benefits, you need to spend a minimum of two hours a week in green spaces.

So now that the health benefits of nature are being recognized and encouraged, how do we create inclusive spaces for people of colour? Groups such as Colour the Trails, Indigenous Women Outdoors, and #DiversifyOutdoors are working to reduce barriers, increase media representation, and elevate the voices of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of colour) outdoor community members. For example, the Nuu-chah-nulth Youth Surf Club increases access to surfing for Nuu-chah-nulth youth by supplying gear, instruction, and transportation.

Today, I see people who look like me in ads for outdoor companies. Though outdoor recreation spaces remain predominantly white, I find solace while scrambling mountains, surfing remote beaches, or paddling the K’ómoks waters with friends whose skin browns like mine. Being in wild spaces is where I feel free to be part of the interconnected cycles of life as a human creature, part of the organization of nature. In the immenseness of wild spaces, I find peace.

And this summer, in the quiet of the breaking day at Comox Lake, I will think of my grandma as I starfish float, breaststroke, and hold my breath under water. I swim for her.