The third in our series imagining how the Comox Valley’s communities could look 20 years from now.

How quickly we can adapt. That’s the underlying message inside historian Kristen Cohen’s new book, 2020: The Year That Changed Courtenay and the World.

The anthropology professor at North Island University traces everything from ubiquitous public art displays to the steady decline of greenhouse gas concentrations back to the COVID-19 pandemic that began in 2020. But rather than using global examples of this dividing line, she focuses on the shifts that occurred right here in Courtenay.

Beyond a realization of how much can change in 20 years, the book also reminds us how events that seemed monumental at the time quickly become normalized. In an interview with the CV Collective (CVC), the author shares her own memories from the pandemic year and life afterwards.

CVC: Humans have a tendency to rush back to the status quo after an emergency. Why didn’t that happen in Courtenay in 2021 and beyond?

Kristen Cohen: It was partly luck, I think. In September 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, Courtenay reviewed its Official Community Plan (OCP). There were all these smouldering issues we had been sort of ignoring: homelessness, racism, climate change, and sustainability. Restarting the economy created an opportunity to tackle them, and the OCP was an outlet for people to express their ideas. Almost a third of the population submitted comments.

What was one of the more innovative ideas that emerged from that OCP?

The reimagining of what a neighbourhood means. With social distancing and travel restrictions in place, we began to put an even higher value on access to nature, outdoor space, and community.

Instead of sprawling suburbs with centralized and distant parks, shopping, and services, Courtenay was one of the first cities to adopt the “15-minute neighbourhood” idea. We envisioned a community where within a 15-minute walk from their home, every resident would have access to groceries, schools, a nature park, an outdoor space for picnics and gatherings, a community garden, and a neighbourhood house offering social services and support. And to a large extent, we’ve succeeded.

This initiative also led to a local renaissance in community and public art installations, a corridor of community farmland following the old E&N railway from one end of the city to the other, and the multi-use trails spiderwebbing all over town.

In researching the book, what surprised you the most?

I had forgotten about all the land we wasted on cars. Looking at a map from 2020 I was shocked at how much space parking consumed in the city. Public transit, car sharing, electric bikes, and active transport were in their infancy; Courtenay was still very much car dependent. There was a large parking lot on the corner of 4th Street and Duncan, right where our permanent food truck and local goods market is now. The complex at the Driftwood Mall, where university students live with seniors? That was one of the largest parking lots in town. Fifth Street was a busy artery, and not for active or public transport, but for cars and trucks. Think about that the next time you’re drinking a beer along the 5th Street Walking Mall.

There must have been some controversy with some of the changes.

The campaign to remove the Dyke Road and let the Courtenay Estuary go wild was definitely contentious. Forward-thinking engineers and environmental groups argued that getting rid of the road was the only way to allow the estuary to buffer the yearly flooding and storm surges inundating low-lying areas of Courtenay. There was a very vocal group opposed to the idea. The issue probably would have gone to court, but the flood of 2025 washed most of the Dyke Road away. It was never rebuilt. You can still see remnants of it just past Kus-kus-sum, where the wetland walkway looks out onto the migratory bird sanctuary.

How did the economy of Courtenay change?

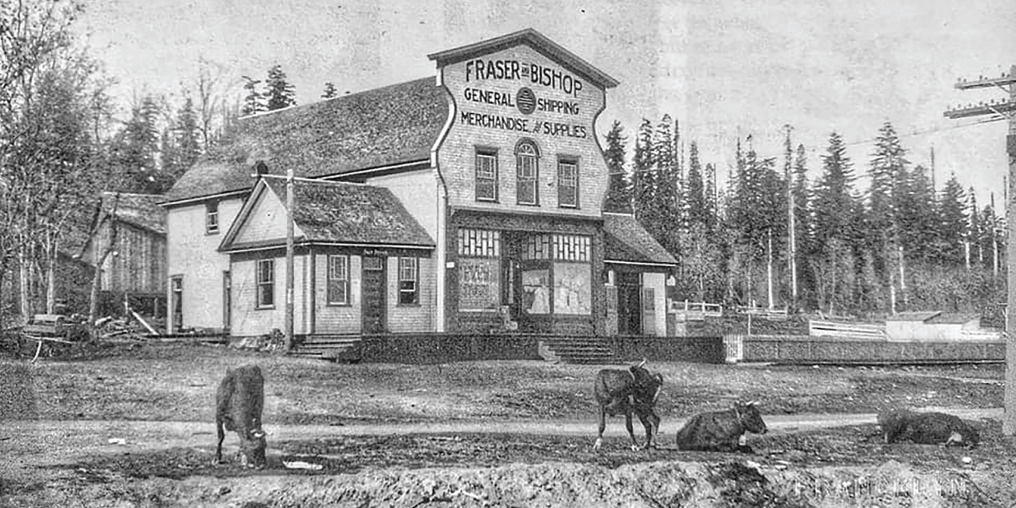

That was one of the most interesting things I learned in my research. For many decades before the pandemic began, Courtenay had been a farming centre. For example, Condensory Road was named for a major milk processing plant that used to be here.

But by 2020, the area had moved away from its agrarian roots. Vancouver Island imported most of its food, farmers were getting older and older (and making less and less money), and land was too expensive for the next generation to buy in. Then the pandemic and lockdown created these food-shortage worries. Suddenly people realized how important local food was. A new local Food Policy Council helped transform the community’s relationship with food and food security. More people started paying the premium for food grown nearby, making it easier to earn a living farming. Programs like the Young Agrarians paired new farmers with old ones to pass along knowledge and land. And North Island College became a university offering climate-resilient and regenerative-farming programs. Nothing shows agriculture’s resurgence better than the Crown Isle lands, where the university’s demonstration fields are. It’s hard to believe that area was an 18-hole golf course not that long ago.

In the book, you talk about the racism controversies and protests during the pandemic. How did that play out in Courtenay?

It put a spotlight on the rights and title of First Nations. Residents of Courtenay realized they needed to show more respect to the K’ómoks people’s territory, particularly around culturally important spots like the confluence of the Tsolum and Puntledge rivers. Tubers and fishermen started to avoid the area. The K’ómoks people returned the gesture by sharing their insight and knowledge about living multi-generationally, connected to the land and water that sustains us.

The shift went beyond Indigenous and non-Indigenous relations. There was a real acknowledgement that we had to work together as a community to solve pervasive and stubborn social issues. The City bought a few of the older hotels and converted them into transition housing to help homeless people get off the street. Vancouver Island Health invested in more mental-health and addiction counselling. Where we sometimes saw nimbyism toward these efforts before the pandemic, afterwards there was almost no opposition.

It truly was the defining moment of the last 20 years, I think. At some point in 2020, the tide changed, we realized we were in the boat together, and everyone finally started paddling in the same direction.

Did you know? The City is reviewing Courtenay’s Official Community Plan that will inform how we as a community grow over the next 10 years. The pandemic is affecting the workplan but the work is continuing at present.

Please learn more and sign up for the e-newsletter to stay up to date at: www.courtenay.ca/OCPupdate