The idea that the dead remain with us in spirit is ancient. Cultures the world over document the presence of ghosts through stories. Regardless of whether you believe in the supernatural, it’s undeniable that the voices of past generations still echo through our communities today.

As daylight dwindles and the heat of summer wanes, autumn emerges as a season of reflection. “Maybe the fall is the time when we can reach back into the dark of Cumberland’s past story?” wonders Meaghan Cursons, who leads the Village of Cumberland Guided Walking Tour. “Since it’s around Halloween, I feel that the veil between here and other times becomes thinner.” She also acknowledges that “there is a dark side to Cumberland’s history—and I think it’s important—steeping into the bones and the core of our community.”

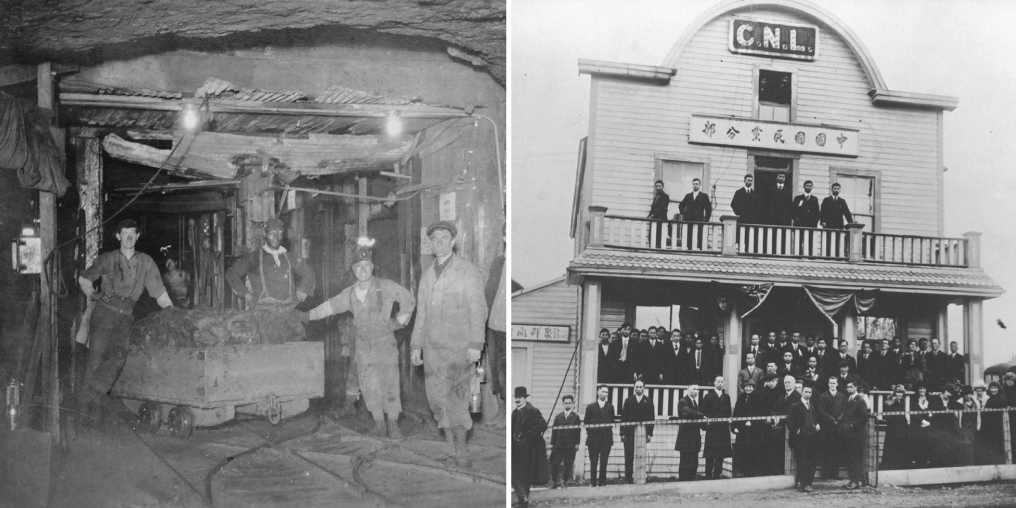

The fall walking tour diverges from the script in order to explore this gloomier side, offering glimpses into the fears, superstitions, and death traditions of Cumberland’s earliest settlers. From the Chinese hungry ghosts, who are tormented by unfulfilled cravings, to the hellish depths of Scottish coalmines, there are certainly many glum tales of death and disparity.

As tour participants stroll past the lively restaurants and beautiful boutiques that are altering the face of Cumberland, Cursons highlights buildings and landmarks that take us back to a more fragile and tumultuous time. They provide a link to eras when life was more tenuous—when flames consumed whole blocks, and lives were lost while searching for dusty, black coal in the belly of the earth. At No. 6 Mine Park, beneath our feet, still lay the bodies of the victims from Cumberland’s largest mine explosion that killed 103 workers.

The chipped paint on the keeling structures of bridal alley, the elegant heritage homes along doctors’ row, and the coke oven bricks that adorn the liquor store provide vestiges of the past that can draw us back through time. The stories that these relics represent also ground us in the present. Venturing towards Comox Lake, the forests have other tales to tell.

The Cumberland Museum and Archives also facilitates the Old Townsites Historic Walking Tour with the knowledgeable Dawn Copeman. “Sometimes you can feel it in the air,” Copeman sighs as she guides a tour group through Coal Creek Historic Park, the site of Cumberland’s past Chinatown. While walking the forest trails you can smell the same earthy scents of the marsh, and leave your footprints on Hai Gai (lower street), the original road which travels past the pavilion, towards the disc golf course, and now winds its way upwards as a mountain biking trail. Watching the generations pass, you can imagine that the trees have stories to share—tales of busy streets, bustling businesses, and a vibrant Chinese culture. At its peak, the community had about 1500 residents, and maps drawn by former residents show restaurants, public houses, gardens, and even a theatre house. Trekking down the dirt roads in 1915 you may have even smelled the rich cuisines of a twenty-course meal being prepared, or heard the rowdy calls from one of the gambling or opium dens. In the absence of family, this largely male community persevered through harsh coal mining conditions, numerous fatalities, and persistent racism. There is certainly a dark side to Cumberland’s rich history; as black as coal, but with various accents of colour that build our historical canvas.

“Do you want to hear about the murder?” Dawn asks as we continue our route. Yes, we do. Firstly, Dawn wants to be clear that Chinatown was generally a tranquil place, but during the peak of animosity between the Chinese Freemasons and the Chinese Nationalist League in 1921, politics shouldered tranquility aside. Imagine, if you will, that president of the Chinese Freemasons, Low Hock Shun, becomes a target for murder. During the appointed day, Low is unable to be found, but the assassin strides into Chinatown’s travel agency and finds his secondary target, the secretary of the Chinese Freemasons, Jain Shing, working behind the front desk. As Jain Shing turns around to write a ticket for passage on a steamship, he is shot in the stomach with a Luger pistol. According to hospital records he died four days later. The murderer was eventually given a not-guilty verdict because of the alleged biases of the witnesses who were members of the Freemasons. The assassin booked passage back to China, but local reports say that he never made it off the ship. “Perhaps he’s Chinatown’s only ghost?” Copeman muses.

This theory is based on the fact that the bones of the Chinese workers are no longer in Cumberland. Interestingly, many residents paid into the Chinese Benevolent Society, which acted as a sort of insurance guild that was created to finance funeral arrangements in the event of mining fatalities. As well as a proper funeral, the arrangements also included the unearthing of the interred bones seven years after their burial in order to be sent back to China and returned to the deceased miners’ village to be properly honoured.

PHOTOS BY CUMBERLAND MUSEUM & ARCHIVES.

As we contemplate the supernatural, we head west on the Wellington Colliery trail where the railroad led to a different community. While Chinatown was largely a bachelor population, the residents of No 1. Japanese Town brought their families to Cumberland. They were well integrated into the community and established many prosperous businesses. As we walk down the trail we pass a large patch of Fuki, a leafy, edible plant that you find only in areas of Japanese settlement. You also walk past the thirty-one Mt. Fuji flowering cherry trees that were planted in memory of the families who were forcibly removed in 1942.

While Pearl Harbor was the beginning of the end for Japanese Town, major fires and the transition from coal to oil acted as the death knell for Cumberland’s Chinatown. Today, as we hike through Cumberland’s beloved forest, lounge on a downtown patio to enjoy a drink, or shred past the mine sites on our bikes, we may spy vestiges of the once booming communities. But whether or not you believe in ghosts, you may feel the nostalgic presence of the people who resided here before, and whose actions created ripples felt even today.