I used to write science fiction (which means I know little about science, but I liked playing with ideas). In one of my stories there was a planet called Lumbercanned, where, for millions of years, the main residents were Vegetarian Rodents of Unusual Size (VROUS), and some people who were their stewards. Another name for the planet was The Fire Swamp, not because this forested wetland was constantly on fire, but because parts of it burned every 250 years or more as a natural process that recycled nutrients and allowed lots of unique species to thrive. This burning was also called “Natural Disturbance Type 1” by a later invention called The Biodiversity Guidebook, which didn’t pay much attention to what the VROUS or the stewards had to do with fire. But that is a different story.

One day, exotic aliens arrived at the Fire Swamp. They came on shuttles made of wood, from a faraway land, which sounds like it would take a long time but it didn’t, really, in the sort of time frame the Lumbercanneders were used to. The aliens made it so there were a lot fewer VROUS by killing them and wearing them on their heads as a warning to others, or perhaps as a warning to males of their own species; they probably weren’t sure themselves, but they liked the way they felt.

The aliens also made it so there were fewer people who were stewards of VROUS and trees, and they tried to make it so the trees never burned, but were all taken away every 60 years. Or sometimes 80. It depended on how they felt at the time.

But then the newcomers found themselves trapped in quicksand, even though there hadn’t been any quicksand in the Fire Swamp before they arrived. They had brought the quicksand themselves, and it was the continuing legacy of colonialism and poor environmental management. The only way out was through Reconciliation and Social and Environmental Justice. And, as the aliens struggled, they had an idea: perhaps the VROUS and their stewards could help?

People are good at getting under beavers’ skins, and not just historically. During some years in the 1970s and 1980s, an estimated high of 1.1 million beavers per year were killed for their pelts in North America. But are beavers also good at getting under our skin?

Ask anyone responsible for maintaining roads, bridges, or predictable irrigation for agriculture, and you will find the answer is a resounding YES. Beaver activity can reduce the amount of water downstream, causing great cost and inconvenience to landowners or managers who have not planned for water-level change.

But under their frustration often lurks a grudging admiration for this resilient rodent that once had a nearly continuous range of over 2.5 million square km—from Alaska to Mexico.

American beavers (Castor canadensis—well played, America) are regarded as a cultural keystone species for many Indigenous peoples, in recognition of their importance for food, fur, and income from trade (after the aliens settlers arrived). They’re also an ecological keystone species, meaning their presence has the power to transform living landscapes.

Beavers build dams to increase available food and habitat. They create deep pools of still water to help them avoid predators and cut young branches to ensure fresh greenery (even in sub-zero winter temperatures). The edges of beaver ponds are perfect for growing young vegetation (like regenerating alder) at convenient beaver height.

They literally create “wet lands” by felling trees with their TEETH (please, pause and think about that)! These ecosystem engineers—indentured labourers, if you’ll pardon the pun—build dams, slow down water, and effectively retain water on a landscape.

Unlike human-created dams, beaver dams maintain the natural seasonality of water flow and tend to stabilize fluctuation of water levels, allowing plants and invertebrates that thrive in more stable, slower-moving water to establish.

Beavers leave small patches of standing dead trees, which create habitats for cavity-nesting birds like buffleheads and hooded mergansers.

Thus, the end result of having beavers on a landscape can be a mosaic of shallow wetlands with high biodiversity, productivity, and ecosystem services.

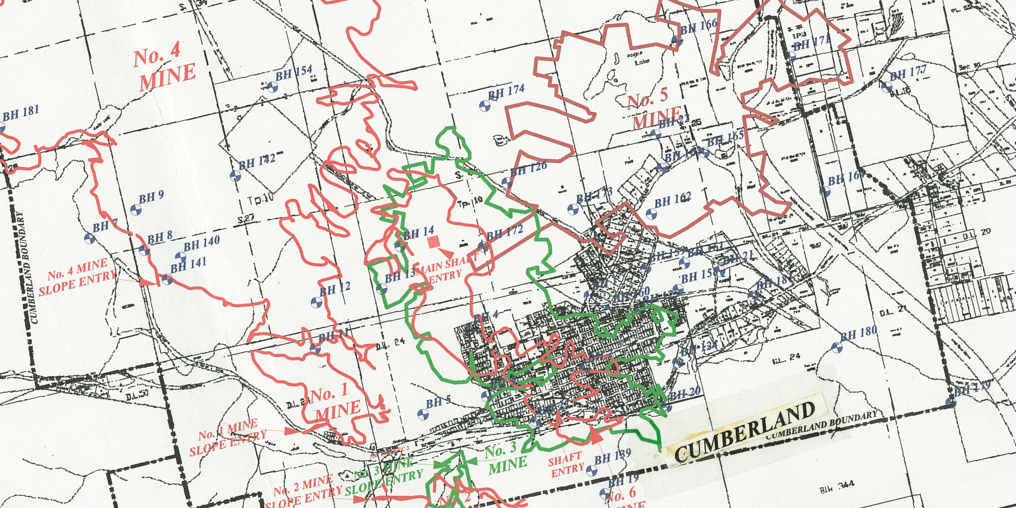

Whether created by beavers or not, wetlands are crucial to the landscape. Patches of wetlands suppress large-scale fires that could otherwise burn through soil and delay regeneration. They can further help regulate ecosystems by filtering environmental toxins and reducing runoff from extreme weather events. The Comox Valley is currently evaluating how to protect and restore its major wetlands around Cumberland, Morrison Creek, Kus-kus-sum, and Merville, so it seems like a natural time to think about beavers.

With a bit of artistic anthropomorphism, beavers can be described as creatures that know what sort of world they want for their babies and set to work creating it. We should value them simply for the example they set for us.