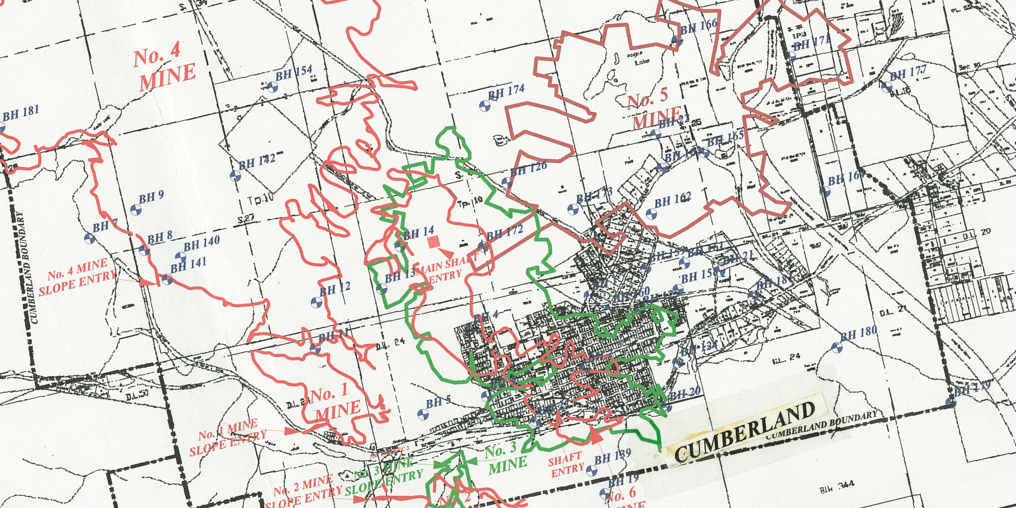

Starting in 1888, a vast labyrinth of extraction tunnels was carved beneath the village of Cumberland, the old Bevan and Puntledge townsites, Comox Lake, and many areas between. When visitors come to the Cumberland Museum and Archives, I tell them not to jump too hard on the road surface in the village, as No. 5 and No. 6 mines and their flooded, acid-leaching, methane-gas-filled chambers are only a few hundred feet below.

Evidence of coal mining is not just below. Dotting the landscape around the Comox Valley are a series of what can look like land “dimples”—hollowed openings into the ground. These are either vertical test pits or boreholes. As many as two hundred of them scar the local landscape, though many are now obscured by brush. Some have collapsed or have been deliberately broken up to disguise the entrances.

These aren’t little holes. According to Gwyneth Cathyl-Huhn, a well-known local geologist and historian: “Every hole in the Comox coalfield was drilled until it got 20 or so feet into the ‘trap rock,’ which was red, weathered, and soft at the top, but dark green and unmistakably hard to drill further down. The depth of the trap rock ranged from 140 feet near the portal of the No. 4 mine to 1950 feet in ‘downtown’ Royston.”

Canadian Collieries drilled the last borehole in the area, CX 204 near Hamilton Lake, in 1953.

Exactly one hundred years earlier, in August 1853, Robert Dunsmuir disembarked from the Hudson’s Bay Company ship Otter, which was moored off Point Holmes. Four Pentlatch guides took him across the estuary in their canoe. He found a spot where coal was exposed on the surface and hand-drilled a sample to assess the extent of the coal seam in “them thar hills.” It turned out there was (and is) a lot of coal.

That first borehole drilled in 1853 was random, based on intuition and luck. It would be years before the coalfield was properly surveyed and mapped. The Hudson’s Bay Company interests segued into provincial ownership; all the subsurface rights for coal in the Comox coalfield were awarded to Robert Dunsmuir in 1887 in exchange for building the E&N Railway (part of a massive land grant encompassing one quarter of Vancouver Island).

While the Dunsmuir holdings—mostly in the Cumberland area—are the best-known local mines, several different groups prospected for coal all over the Comox Valley before Dunsmuir’s “great land grab.” Claims were made along the Puntledge (including one for the five miles from Brown’s River to modern-day Comox), Tsolum, Tsable, and Cruickshank rivers, and at Comox Lake, Union Bay, and Buckley Bay. Baynes Sound, whose namesake mine began production twenty years before the Dunsmuir mines, closed in 1878 due to lack of capital and slumping coal prices.

Back to the boreholes. They would have been much more visible and well known during active mining days than they are today. As a boy in Cumberland in the late 1930s, Rocky Williams and his buddies roamed the streets on hot summer days, fishing in the creeks or at Comox Lake, picking berries in the woods, and getting into a little mischief. When local historian Gwyn Sproule spoke to Rocky about his childhood misadventures, he recalled how he and his friends would visit the active boreholes and throw in matches to see if any methane gas was leaking from the opening. Instant ignition would shortly be followed by the arrival of the fire department to extinguish the blaze. Fun (if slightly dangerous) memories.

Childhood shenanigans made way for a long and distinguished career as a surveyor. In retirement, Rocky turned his boyhood interest in the boreholes to good use—pursuing a quest to re-survey 130 boreholes between Cumberland and Bevan, confirm their locations using the original survey pins placed by the collieries, and map them into a more modern coordination system. Rocky died in 2021 with his mission complete.

ROCKY WILLIAMS (ON BIKE) AND HIS FRIENDS, INCLUDING BRONCO MONCRIEF (IN TWO-TONE ZIP SWEATER), COURTESY OF WILLIAMS FAMILY

Nowadays, very few people know the locations of the boreholes—and the survey pins you need to find them. The first survey pin, numbered CX00, was placed along the colliery railway line near where the Cumberland BMX park is today. The second pin, CX01, is downtown, somewhere near the Waverley Hotel.

The only remaining maps that show the locations of all the survey pins and boreholes were once displayed on eight large plans, each nearly the size of a sheet of plywood, in the basement of the Cumberland Museum. The plans are currently in storage, and, even with Rocky’s map, the boreholes are difficult, if not impossible, to find without the right tools or the exact location of CX01.

And CX00, the very first survey pin? It is buried, like treasure, not giving many clues to the coal beneath our feet.

FEATURED PHOTO COURTESY OF CUMBERLAND MUSEUM & ARCHIVES