Have you ever wondered what your body is physically and mentally capable of handling? I asked myself this question in 2017 when I first heard a friend was attempting to thru-hike the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT). Although I’d never before heard of thru-hiking (finishing the entire trail within a year), I immediately felt compelled to attempt it.

This 4,240-kilometre-long hike starts on the Mexican border in Campo, California, and ends in Manning Provincial Park, British Columbia. Along the way, it racks up 149,000 metres total ascent and descent. That’s like ascending and descending Mount Everest from sea level approximately 15 times!

What better way to celebrate my retirement?

I spent a couple years preparing: I read books, blogs, and articles, and watched hundreds of hours’ worth of YouTube videos. I researched and obtained the lightest gear possible that still promised safety and comfort. I cycled and did strength training, hot yoga, and, of course, lots of hiking with a pack. While this was going on, I waited for my permit.

To help preserve the PCT, access is tightly limited by the US Forest Service and permits are awarded via a lottery system. The pandemic forced me to cancel my original 2020 permit, but after waiting another two years, I received a new date: April 14, 2022.

I started my adventure two weeks after my 67th birthday, which made me one of the more “mature” hikers out here: most others were in their late twenties or early thirties.

The PCT has five major sections, and only around 20 per cent of thru-hikers complete the entire trail in any given year. But based on my previous hikes and experience from my forestry career I felt confident I could do it.

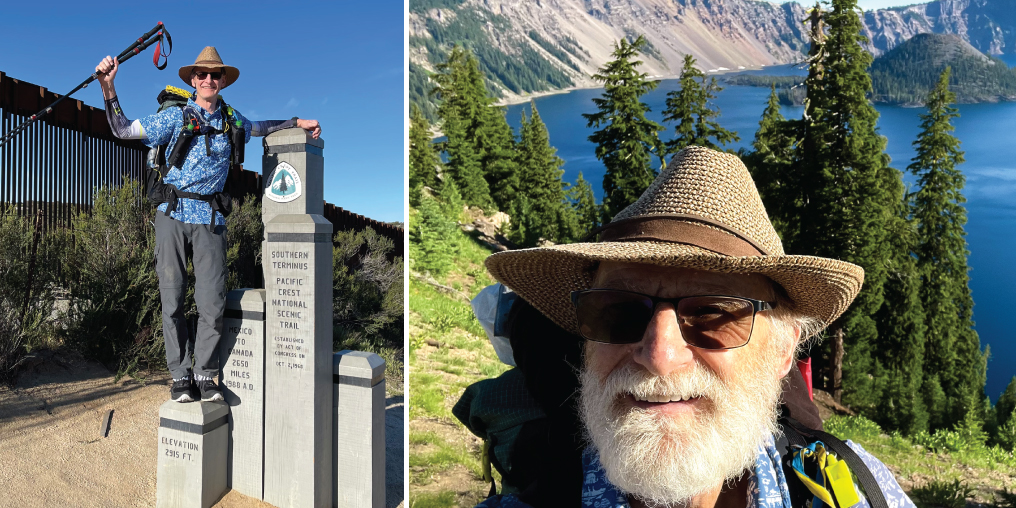

LEFT: PCT SOUTHERN TERMINUS WITH MEXICAN BORDER IN BACKGROUND RIGHT: CRATER LAKE, SOUTHERN OREGON

It took me 47 days to traverse the 1,100-kilometre California desert section, which—although hot and dry—has none of the rolling sand dunes you might expect. It was, however, abounding with rattlesnakes, lizards, and ground squirrels. The trail crosses sagebrush scrub, Joshua tree woodlands, chaparral, and the high-elevation subalpine forests of Mount Baden Powell and Mount San Jacinto. I felt comfortable in this section, and making new friends on the trail was very easy. Early on, a fellow hiker suggested my trail name: “Aloha,” for my Hawaiian shirt.

I quickly learned to be thankful for trail angels: volunteers who service water caches, provide food and refreshments, and drive hikers to and from trailheads.

After more than a thousand kilometres of desert, I was ready for a change of scenery, and the Sierra did not disappoint. This 640-kilometre section has numerous mountain passes over 3,600 metres, including the highest point on the entire PCT: the 4,000-metre Forester Pass. Although the Sierra Nevada is often still snowbound in June, this year there was only the occasional patch on northern exposures.

Granite cliffs bordered the valleys I was hiking through; the trail meandered above and below treeline. It was magical at times to look from one pass to another and not see anyone around. I realized what a speck I was in this vast wilderness.

It was early June, and with longer days (and cooler, thanks to higher elevation), 30- to 35-kilometre days became my norm. I had a six-day food carry through this wild, thinly populated area; I was thankful for the abundant lakes and streams reducing the amount of water I had to carry.

In parts of the 980-kilometre Northern California section, the landscape had been deeply scarred the year before by the catastrophic Dixie Fire, which had consumed more than 390,000 hectares. At times, the trail was covered with two or three inches of soot.

Near Lassen Peak and Mount Shasta, the terrain was a vast expanse of lava fields, the trail made of broken pieces of lava. The footing was terrible. Even so, 40-kilometre days were now a regular occurrence, with my longest day being 48 kilometres.

SUNRISE ON MT. ADAMS IN SOUTHERN WASHINGTON

After 87 days and 2,142 kilometres, I finally reached the half-way marker—but I wouldn’t get out of hot, dry California for another 560 kilometres.

On Day 107 (July 30), I woke up to thick smoke and falling ash. Ashland, Oregon, was living up to its name. The segment of trail I had recently walked was now closed in both directions due to a fire. I felt lucky to have missed the closure, but it was depressing to hike through smoke for the next few days.

Later in Oregon, two other fire closure detours took me away from my planned route, on to roads, railway, and pavement, adding many kilometres to the trip.

But the state had plenty of highlights through its 740 kilometres, like the incredible blue-green waters of Crater Lake, Eagle Creek’s Tunnel Falls, and Timberline Lodge at the base of Mount Hood, where I savoured a meal before camping overnight.

Washington state was absolutely spectacular. Climbing out of the Columbia River gorge was tough mentally, but my morale picked up again in the resupply village of Trout Lake, thanks to town food, beer, and R&R.

This 780-kilometre section of the PCT was one of my favourites. Views of Mount Adams and Mount St. Helens, covered in snow, were amazing. Hiking the Knife’s Edge in the Goat Rocks Wilderness on a clear, calm day, with Mount Rainier as a backdrop, was out of this world.

After a few days in Leavenworth, WA, with my good buddy Kevin from Victoria, I made my last push for the Canadian border, my dream of hugging the northern monument within reach.

Sadly, it wasn’t meant to be. After lightning storms ignited several fires between Windy Pass and the Canadian border, the US Forest Service closed that section of trail just before I arrived.

I reached Windy Pass on day 152. After a continuous foot path of 4,205 kilometres from the Mexican border, I was 40 kilometres short of reaching my goal.

I had hiked as far as I was allowed to hike on the PCT and yet there was a feeling of emptiness, an unfulfilled goal, and the first sense of loneliness when there was no one else around to celebrate the end of my hike.

And yet, it had been apparent from the get-go that completing the PCT is about much more than just body, mind, and vistas. For me, it turned out to be about the camaraderie among fellow hikers; the kindness shown by trail angels; the support and two visits from my buddy Kev; the encouragement from family and friends at home; and especially the love and care from my wife before, during, and after my hike. I saw vast areas of wilderness that many people do not get to see. I encountered rattlesnakes, several black bears (including a sow with two cubs in tow), bugling elk, and mountain goats.

And I don’t have to wonder any longer; I proved to myself that I was capable of handing the physical and mental challenges of the trail. I heeded the advice of the experienced and always had small goals along the way that I knew would end up giving me what I had set out to do.

My PCT thru-hike was truly a magical journey that I will never forget.

LEFT: FORESTER PASS (ELEVATION 4,025M), HIGHEST POINT ON THE PCT RIGHT: BURNEY FALLS, NORTHERN CALIFORNIA