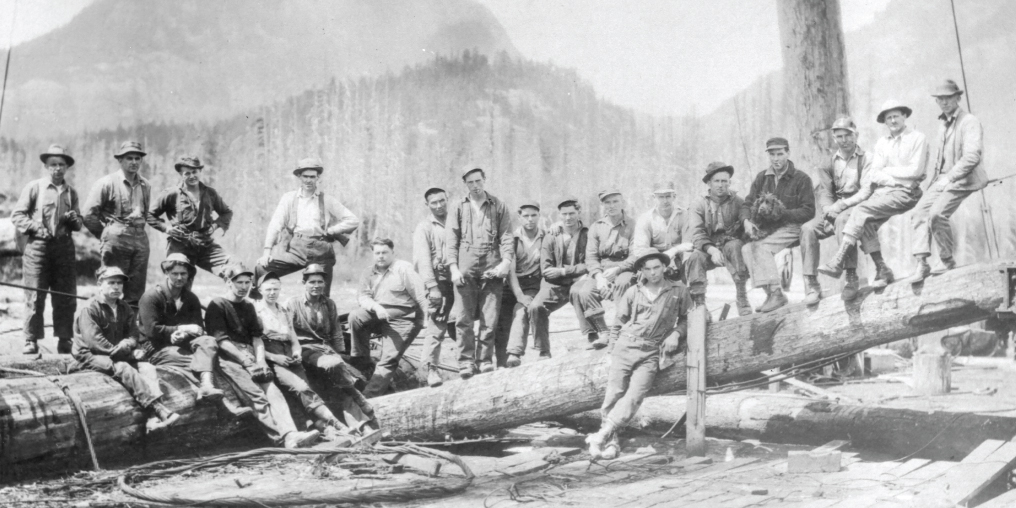

While looking at a 1931 photo of a crew of men seated on a logging raft, long-time Cumberland resident Karl Cameron reminisces about the stories his father, Pete (sixth from the right, standing, in the photo), told him about the old logging days in the Comox Valley. “My dad started working for Comox Logging [as a chokerman] when he was 15, so he was around 18 or 19 when the picture was taken,” says Karl.

“I used to laugh when I was a kid, when he would tell me they would stay on the A-frame in the bunkhouses Monday to Friday and go home on the weekend. I would say to him, ‘You were only two miles from home; why didn’t you go ashore and sleep at home?’ He never did actually give me a straight answer.”

Logs were lashed three layers deep to form a platform 200 feet long, 150 feet wide, and 12 feet high—enough lumber to build a hundred houses. Housing upright steam-powered winches called “donkey engines” and a giant A-frame, the raft was towed over the water to log the steep sides of Comox Lake between 1929 and 1934. Two hundred men were housed in floating bunkhouses that followed the A-frame around the lake.

Karl says, “They logged from the bottom of the lake up the sides… all around. When I go out to the lake or up the lake, it still amazes me how tough and dangerous it must have been.”

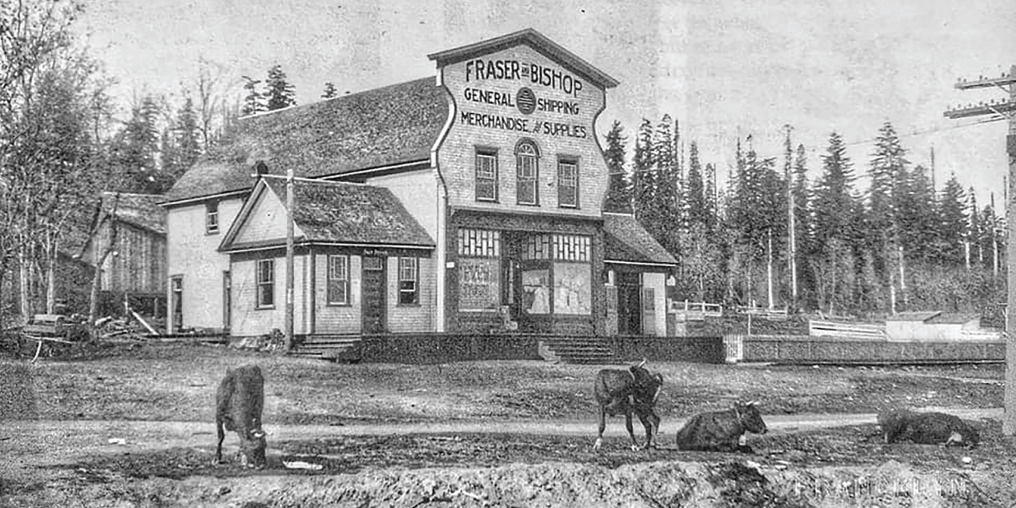

Comox Logging was established in March 1910 as a subsidiary of the Canadian Western Lumber Company. It logged 135,000 acres of land on eastern Vancouver Island between the Comox Valley and Campbell River to feed Fraser Mill in New Westminster, which could process 700,000 board feet of lumber a day.

Many people who have seen copies of the photo have never noticed the brown dog sitting on the lap of a man dressed in brown (fourth from the right), but Karl remembers his dad telling him there was a dog called Nellie who belonged to one of the men on the A-frame crew: “Nellie died and they buried him at the camp next to the Cruickshank River and all the crew sat around singing ‘Wait ’til the sun shines, Nellie.’” Pete Cameron left his logging career behind not long after the photo was taken. In 1934 he became a barber; he retired on his 65th birthday in 1977.

It must have been nice for the men to have a little canine companionship, since the work was hard and dangerous, all year round. All the timber was felled and bucked by hand to predetermined lengths of either 24 or 40 feet. (Chainsaws weren’t widely used until after WWII.) Then the logs were moved along skylines down to the water.

To picture this, imagine something like a giant clothesline 150 feet in the air—that’s the skyline—stretching 1500 feet from the peak of the A-frame to a tall stump way up the hill. Instead of flapping laundry, though, it was huge felled logs that were attached to the cable. The size and weight of the A-frame provided leverage and ballast while the donkey engines provided the power to yard (move) the logs into the water. It took skill to attach the logs, and nimble, cat-like reflexes to get out of the way of the skyline.

The harvested logs were floated to the head of Comox Lake and loaded on flatcars, then transported nine miles downhill by rail in relays of 25 or more 40-foot flatcars to Royston—two or three trips a day if the woods weren’t too dry or the snow didn’t stop operations. Then the logs were boomed before being moved across the bay to Goose Spit, then tugged across the Georgia Strait to the mill on the mainland.

At one point the Comox Logging and Railway Company was the largest logging company in the British Empire. Locally it was a major employer for over 50 years, with a total workforce of 400 men. Eventually, though, the last logging train came down Courtenay’s 5th Street in 1956, and active operations moved down to Ladysmith. Trucks replaced trains and all the rail lines were dug up and removed. But evidence of this era—beyond springboards in old stumps and rusted steam donkeys in the woods—is still all around us.

The floating bunk houses and A-frame platform were moored permanently in 1934, and a stationary camp was built at Comox Lake with housing for families, a school, and other services. It lasted for a short time, while more inland logging was carried out. Old pilings still reappear when BC Hydro drops the levels at the dam, or during an especially dry spring.

Royston Wrecks are made up of donkey engines scuttled with old ships as a breakwall that was originally built to protect the log booms.

Comox Logging Locomotive No. 2 sits on display on Cliffe Avenue at the old Tourist Information Bureau site.

And the memory of Nellie the dog lives on in an old photo.

A way of life, a community, that no longer exists. Gone, but not forgotten.

PHOTO: CREW OF 22 MEN AT COMOX LAKE. 1932. C150-066