I grew up in a cheaply thrown together subdivision in Fort McMurray, erected during Alberta’s oil boom. Surrounded by fast food restaurants, blaring televisions, overflowing garbage cans, and angry people, something crucial was missing. I felt lost in a skipping record culture that doesn’t seem to learn from its mistakes. Years later, working at a manufacturing office in the industrial district of Victoria, I was weary of arbitrary deadlines, printing errors, and shipping delays. I was having a recurring dream of seeing a cougar in a city suburb and out in the wild. I was ready for something weird and wonderful to come along.

A family member who’d visited Boat Basin informed me and my partner Neil that there was a job opportunity there, and shortly after we became caretakers of Cougar Annie’s Garden, 33 miles northwest of Tofino, accessible only by boat or floatplane. We were hired by Ecotrust, who was managing the area, and by Peter Buckland. He started the Boat Basin Foundation to maintain the 117 acre property, open a research facility, and preserve the memory of a single determined settler.

“Cougar Annie” was born Ada Annie Jordan in Sacramento, California in 1888. She lived throughout Canada as well as South Africa and England before moving to Clayoquot sound’s Boat Basin in 1915 with her first husband. She gave birth to 11 children (three of whom died at birth) before he died in a fishing accident. Following his death she began placing newspaper ads looking for another husband, and remarried on three more occasions.

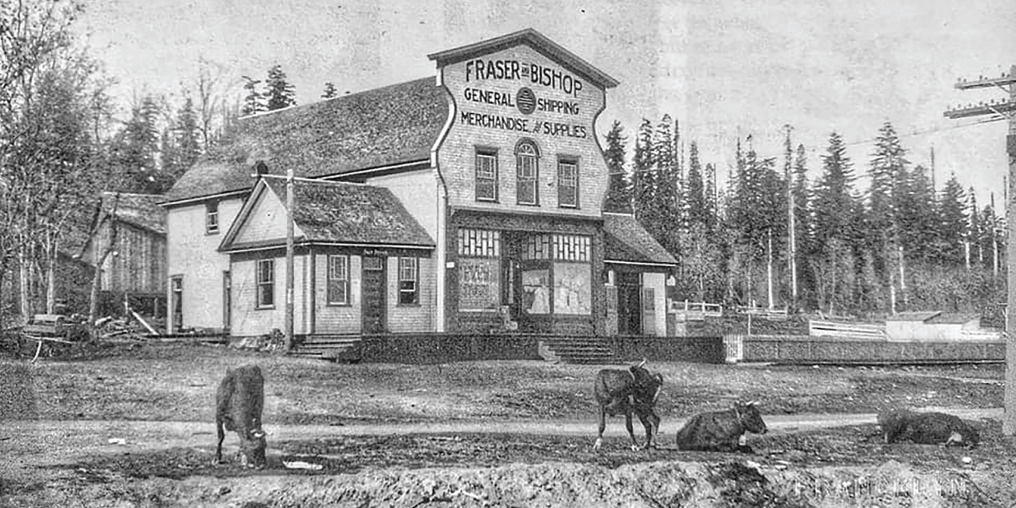

She was a skilled markswoman. To protect her children, orchard, and livestock, she trapped and shot dozens of bears and cougars, which led to her moniker. In her later years she’d greet you at gunpoint and, if she liked the calluses in your handshake, invite you in for tea and fresh baked cookies and request you call her granny. She’d also coerce you into purchasing stamps to make her hard won post office and store, which she tirelessly petitioned for and struggled to keep, look busier.

Ada rarely left her homestead. The Steller’s jays and ravens kept a watchful eye (out of the scope of her rifle) as she worked her strange magic, carving out and expanding her working garden from the rainforest bog and shipping her bulbs and tubers all over the world. She outlived her three subsequent husbands and three of her sons. In 1981, she sold her land to Peter Buckland with the agreement that she could stay on, and he hired caretakers for her. In 1983 her children agreed she should live closer to civilization, and she died two years later in Port Alberni at the age of 96.

Neil and I worked in the garden and guest cabins, and on waterline and trail maintenance. We also led historical tours of the lake and garden and through the ancient rainforest and bog trails. We were off the grid, heating our water on the woodstove and hanging our laundry. We lived in the middle of that garden for close to three years, and during that time I wrote many songs and then a one-woman show about Cougar Annie. Since relocating to Southern Vancouver Island, I’ve had another recurring dream. I’m walking on the lush and mossy ground, listening to the ocean and waterfalls with wolves howling in the distance. Suddenly I realize they are building fast food restaurants and subdivisions nearby. I wake, relieved to find it’s just a dream.

Remote places are an important antithesis to our convenient culture. It took a few years of living on the outer edge of my culture, in a tenacious survivor’s garden, to give me a renewed sense of self and my place in the world. It’s the existence of these places that give me hope for the future.