The gritty exfoliation of sand between toes, the softness of dewy grass underfoot, the wet flecks of mud that spatter my partner’s feet while running the trails in open sandals: these sensations and images are etched in my memory—all reflective of favourite days spent outside with feet directly knowing the earth.

That first barefoot moment after winter, as the frost folds into spring, creates an instant, tangible connection to the earth, a sensation that continues to call us. In her poem “Peonies,” Mary Oliver encapsulates this feeling: “Do you also hurry, half-dressed and barefoot, into the garden … ?” We are called to nature, to live as unbound as possible, without the thick separation of a shoe—somehow knowing deep within ourselves that the earth is meant for us, that there are few things more visceral or beneficial than bare feet in the dirt.

This feeling has been conceptualized as “earthing.” Recently, scientists have documented it. One example is the 2021 article in the Journal of Environmental and Public Health titled “Earthing: Health Implications of Reconnecting the Human Body to the Earth’s Surface Electrons.” The research observes that our modern lifestyle separates us from contact with the earth and that “this disconnect may be a major contributor to physiological dysfunction and unwellness.”

In contrast, when we do slip off our shoes outside, the benefits can include better sleep—perhaps you’re thinking of those deep, calming sleeps on a camping trip if your mat is comfy enough—and even reduced pain. Thus, going barefoot often is not simply an act of childish play; it is an act of reckoning to reclaim the relationship we have with the earth, an attempt to strengthen our mental well-being.

The Journal article explains that we are, in the simplest terms, being grounded—tapping into a “surprisingly beneficial, yet overlooked global resource for health maintenance, disease prevention, and clinical therapy: the surface of the Earth itself.” This benefit has long been overlooked, out of sight, much like the earth pin in an electric plug, a hidden but vital protection against danger.

While this concept may be new to scientific research, the idea of earthing oneself is not new. In Celtic mythology, in Maori culture, in First Nations tradition, and in yogic philosophy there are numerous beliefs and cultural acts that integrate the human body with rich loam or dusty ground.

In Scotland, there is discussion of the healing and wisdom that stem from ancient Celtic traditions in which women would climb into caves, into the earth, into the sea—and listen, awaiting transformation. If you practice yoga, you understand the importance of the asana Tadasana. This “mountain pose” represents sturdiness in stillness, feet firmly planted, eyes closed. It is the chance to settle in the midst of dynamic movement.

Although the modern world moves at lightning speed, we have not lost the ability to connect with the earth. It’s in our nature, our personal histories, our blood. We can experience the nerve end opening sensation of quietly standing on soil. This earthing behaviour allows the frenetic energy of our lives to lessen. In this world, it’s imperative we seek out the pause; stillness is a radical act and earthing restores us.

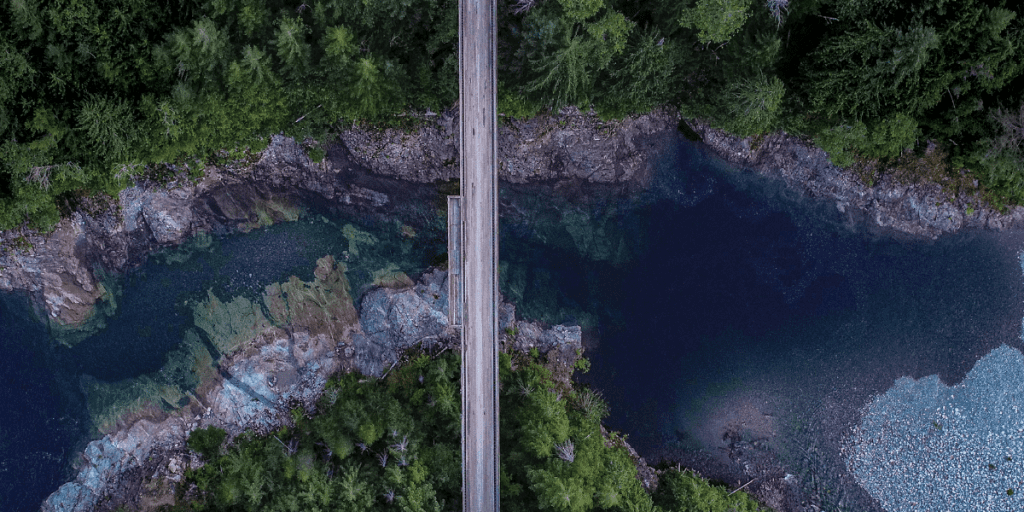

We’re fortunate in the Strathcona Region that a few turns down a trail may lead to an empty grove, an uninterrupted view. There are places where the people are sparse and the trees take over. That lends itself to an opportunity for settling, for weaving yourself back into the landscape. The surge in interest in mycelium networks, or the mother tree concept, has heightened our awareness of the interwovenness of things beneath our feet. It’s paramount that we have a cultural understanding of a place, a respectful relationship to those who came before us.

This interweaving of earthing with an understanding of the history of the land we’re on creates a healing balm in the crises we face. It shows reverence for what’s beneath us and results in a stronger collective stewardship of this place.

I hope that you’ll consider spending more time outdoors barefoot, in stillness, slipping from the busy into reverie, discovering a deeper intimacy to your own sense of self, to the world around you, to all that came before you in this place, and treading softly when the time comes to move.