“A river is water in its loveliest form; rivers have life and sound and movement and infinity of variation, rivers are veins of the earth through which the lifeblood returns to the heart.”

– Roderick Haig-Brown

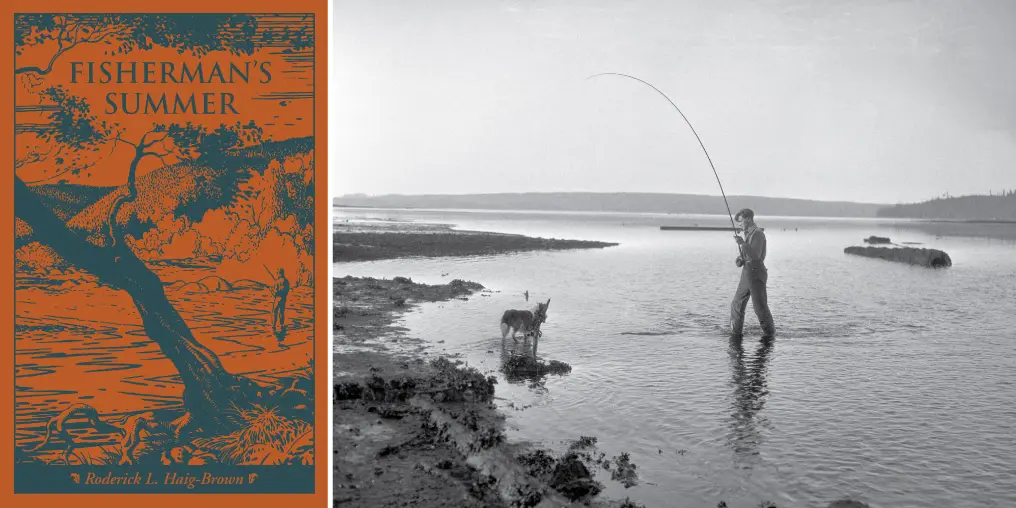

Roderick Haig-Brown was many things—hunter, fly fisher, judge, and University of Victoria Chancellor. He was also a prolific author, penning enduring classics like A River Never Sleeps, To Know A River, and Measure of the Year. Haig-Brown, who lived for many years with his family alongside his beloved Campbell River, wrote about rivers and fly fishing with a sensitivity and intuition that resonates with readers today. Most of all, and perhaps least appreciated, is Haig-Brown the conservationist with a tongue as sharp as a barbless hook.

Roderick Haig-Brown’s early years

Born in Sussex, England, in 1908, he spent his teen years learning to fish and hunt with family friends, who were gamekeepers, on the estates of wealthy English gentry. His father was killed in World War I and, in 1921, his mother enrolled him at Charterhouse School. Haig-Brown was a restless and rebellious young man; he was soon expelled for drinking, making mischief, and sneaking out of the dorms.

He went on to join his father’s military regiment, but strict army life was as unappealing to him as boarding school had been. The family tried in vain to channel the young man into the predictable life of the British civil service. Instead, an uncle’s invitation to visit him in Seattle proved to be a game-changer. Landing in the Pacific Northwest, he was freed of England’s stuffy classism—before him lay a rough, relatively wild world. He started working at logging camps in Washington state before heading north to Vancouver Island. The tall trees, clear streams, and bountiful ocean resonated deep within him. He logged, crewed on commercial fishing boats, and guided sport fishing excursions. These hands-on experiences compelled him to think deeply about his relationship with nature—a narrative that would define his life.

Haig-Brown returned briefly to England, but the formative times he had in the woods and on the ocean pulled him back to Vancouver Island. In 1936, he settled with his bride, Ann Elmore, on the banks of the Campbell River. They built a small farm with a cow, goats, and a large garden. They raised four children on this idyllic homestead with the hypnotic sound of the Campbell River a constant in the background. By then he was working on his third book, one of nearly 30 books he would publish in a prolific career along with 200 essays and speeches.

A forward-thinking conservationist

Haig-Brown had developed both a profound respect for nature and a keen insight into humankind’s capacity for ecological destruction and greed. For Haig-Brown, being on a river was one of the most rewarding experiences in life, whether he hooked a fish or not. His writings returned to this idea many times

In 2016, in a series for The Tyee, journalist Andrew Nikiforuk quotes a particularly noteworthy 1965 speech Haig-Brown gave to the BC Author’s Association at Victoria’s Empress Hotel.

“The shoddy, uncaring development of our natural resources, the chamber of commerce mentality, which favours short-term material gain over all other consideration” was how Haig-Brown characterized the decisions of the then-ruling W.A.C. Bennett’s Social Credit government.

He went on to accuse politicians of possessing a “trivial provincial mentality” that sought “petty advantage at a cost to the commonwealth.”

LEFT: BOOK COVER COURTESY OF HARBOUR PUBLISHING. RIGHT: PHOTO COURTESY OF MUSEUM AT CAMPBELL RIVER, 004519.

FEATURED: PHOTO COURTESY OF MUSEUM AT CAMPBELL RIVER, 002480

Haig-Brown’s speech must have raised some eyebrows. After all, this was the can-do era of the mega-project, a time of building big at the expense of ecological integrity. Industrial logging was scaling up and whacking down forests from valley bottom to mountain top. Large commercial fleets of trawlers were voraciously scooping up the ocean’s bounty. Engineers were designing huge, valley-flooding hydroelectric projects. In the political mainstream, this was progress.

But the most foresighted and unnerving thing about Haig-Brown’s speech, notes Nikiforuk, is its relevance more than 50 years later.

Viewed through a modern lens, Roderick Haig-Brown seems almost larger than life. A 2002 academic paper in the Pacific Historical Review called him “the foremost conservationist in British Columbia from the late 1940s to the late 1960s,” who “fought conservation battles and promoted ecological ideas during a period of aggressive industrial expansion into the province’s resource frontier.”

He was adventurous and creative; a lifelong hunter, fisher and homesteader, as well as a forward-thinking conservationist and community leader.

A tribute from one poet to another

In 1974, the late Canadian poet Al Purdy wrote this about Haig-Brown:

“He’s so respected by other people that I felt incredulous when talking to them, and said to Haig-Brown himself when I met him, ‘You ought to have a halo, an angel’s halo quivering over your head.’”

Angelic likely was not an adjective Haig-Brown would have ascribed to himself, but it was Purdy’s tongue-in-cheek tribute from one poet to another. After all, Haig-Brown could turn getting skunked on a river into a transcendental experience: “I remember the good evenings I have fished, even the ones that realized material hopes not by the fish that came to the fly, but by the colour and movement of the water and sky, by the sounds and scents and gentle stirrings that were all about me.”

Those are words to live by.