The kiln has been firing for six hours. Brilliant orange light is emanating from every crack in the brickwork. The roar from the gas burners is relentless and masks all others sounds. 1200C shows on the temperature gauge. A concoction of hot water and dissolved soda ash is ready in my garden sprayer. It’s time to paint with fire and soda.

Soda firing is my passion. The majority of my ceramic work is fired in this challenging and unpredictable manner. The soda mirrors natural forces in the way it flows through a kiln. Like nature, it is never predictable. There are only some parts of the process I can control—which clays and glazes I use, how much soda I mix, and the way I load the kiln—but in each firing the soda will find its own way.

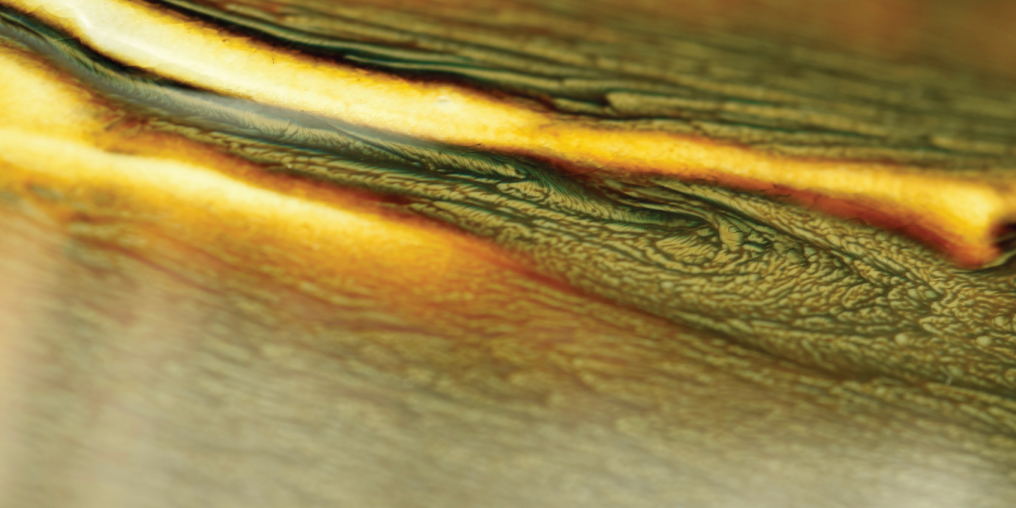

When sprayed into a kiln at high temperature, soda turns into a vapour and is carried with the flame and extreme heat. Chemically it combines with silica and alumina in the clay body to produce a durable, hard glaze. Flowing like a river, the vapour sticks to and transforms every surface into a myriad of textures and colours.

Unloading a soda kiln is one of the most exciting moments of my art practice. I occasionally experience a WOW moment, when a piece emerges that makes me smile deeply or laugh out loud with delight and surprise. These moments fuel my drive to continue exploring. Can I do something like this again? What will happen next time? After unloading, I complete the final finishing on each piece, at the same time assessing how each one feels in my hands. I look more closely at the surfaces created by the soda and fire. I begin to recognize natural forms and forces that surround me—the ocean, mountains, plants, waves, wind, rain and sun.

Reflection after a firing starts the process that brings me back to the potter’s wheel. As I make each new piece, questions emerge. How will this form feel in my hands when I’m using it? How can I place the piece in the kiln to react with the soda vapour and create an inviting, visually exciting surface? How might it capture something of the natural world I inhabit? Each piece goes through many stages after it is formed: trimming and application of textures, drying, first firing to a ceramic state, washing, glazing, and finally loading into the soda kiln. I am ready to paint again.

The last of the soda concoction has been sprayed into the kiln. It is reaching its hottest stage, almost 1300C, and is glowing yellow orange. As I open a spyhole I can see my pieces dripping with juicy soda glaze. With a long metal rod I extract a bright orange ceramic ring. This little ring will tell me if the firing is done, if the soda and fire have worked their magic. Once I am satisfied, the burners are turned off, the kiln is sealed and I wait. Tomorrow I get to open the kiln and reveal its gifts.