The Vancouver Island marmot has lived on Vancouver Island for hundreds of millennia. In all that time, it has only ever lived on this island. Nowhere else in the world.

However, by 2003, the wild population of marmots on the Island had plummeted to five tiny colonies (26 individuals in total) in small pockets of alpine meadow. Due to extensive habitat disturbance from human activity, extinction looked likely for Marmota vancouverensis.

These cat-sized cousins of squirrels are cute by any measure—furry and chocolate-brown, with white noses and underbellies. They tussle and affectionately touch noses, and they watch over each other, communicating to family members with distinctive calls and a whistle that pierces the atmosphere of their habitat when danger is near. In the early 2000s, that whistle was very nearly lost from the Island’s mountain chutes and bowls forever.

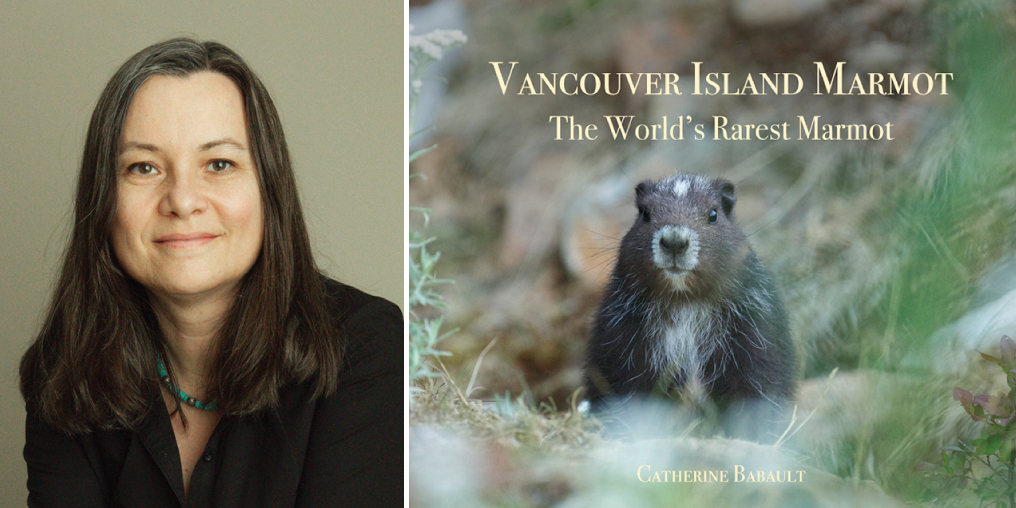

Catherine Babault has lived on Vancouver Island for much less time than marmots have—just ten years. Like many of us, she came for nature. “I love being by the sea, and I love the diversity of the wild landscapes on Vancouver Island,” she says. Passionate about wildlife photography, Babault initially sought out opportunities to shoot big mammals, especially bears and elk. Five years ago, she committed to turning her pastime into a profession, and at about the same time, she became aware of the Vancouver Island marmot and its status as the rarest endemic mammal in Canada—and one of the most endangered animals in the world. Her interest in what she describes as “charismatic creatures” was piqued.

Fortunately, by this time, the Vancouver Island Marmot Recovery Foundation—established in 1998 when the plight of the marmot was first discovered—had been doing hard work for almost two decades. Babault contacted the foundation to ask if she could go into the field with them during their summer marmot research and recovery work on Mount Washington, and in the summer of 2021, she was able to observe and photograph a group of adults and their young. In order to avoid disturbance to the animals and their meadow habitat, she will not disclose the location.

Ethics are at the core of Babault’s work photographing wildlife and teaching nature photography to others; she’s a registered member of 4VI, a Vancouver Island tourism sustainability program. She studies the biology, tracks, and habitat of each species to better understand them before photographing them.

While observing and shooting the marmot colony, she used a telephoto lens to maintain a safe distance. Even so, she washed her clothing and all her gear before going into their habitat to prevent passing on any pathogens to these very endangered creatures. She also wore a mask. “My research, ethical approach, and patience were rewarded with images of marmots play-fighting, feeding, resting, grooming, and caring for their young,” she says.

Her charming images of marmots among alpine wildflowers can be found in the book she published in December 2022, titled Vancouver Island Marmot: The World’s Rarest Marmot. A section of the book written by Adam Taylor, the Marmot Recovery Foundation’s executive director, explains how the work of the foundation and its partners, including the Toronto Zoo and the Calgary Zoo, is successfully increasing the wild marmot population. Through a captive-breeding program, 600 juveniles have been introduced into various Island mountain locations over an 18-year span.

From 26 individuals in 2003, the population has grown to 26 colonies with a total of 250 marmots. Taylor writes that this is still a small population and the Vancouver Island marmot remains at risk, but, because of the successes to date, there is good reason for optimism.

The species’ very uniqueness presents challenges: they’ve evolved to rely on specific plants that grow in the alpine meadows along the Island’s rugged spine. Each meadow can support only a small colony, so when juveniles disperse to start new colonies, they need safe ways to do so and safe places to go. Thanks to the foundation’s advocacy, the province of British Columbia, Mosaic Forest Management, and Mount Washington Alpine Resort have protected certain areas suitable for re-establishing marmot colonies. A critical piece in the marmot’s long-term survival will be the ongoing protection of this habitat.

Much has been done by organizations and individuals to save the Vancouver Island marmot, and the work continues. The public can support marmots through the “Adopt-a-Marmot” program and by reporting any marmot sightings to the foundation.

Catherine Babault continues her research, books—her first published book featured her images of Vancouver Island wildlife—and ethical nature photography workshops and tours. She hopes to inspire young people to become biologists who study and protect wildlife species and habitat.

As a professional photographer, she does her part by taking pictures and telling everyone about these remarkable animals and their vulnerability. “Most people don’t know,” she says, “and they should.”