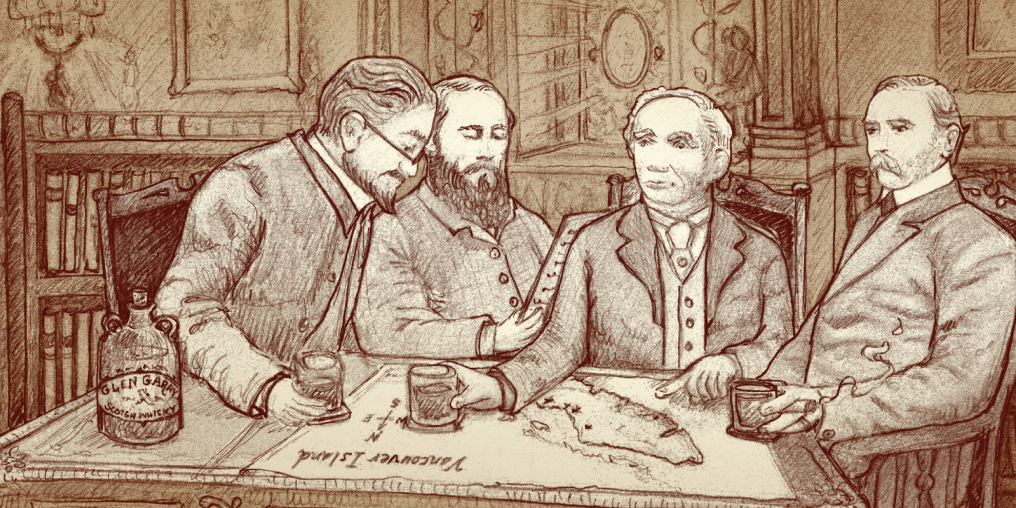

You know the expression, “Never trust a man with a moustache?” Well the same goes for a wealthy man in a top hat. Put a group of them together in a room and bad things can happen, like decisions that ignore the interests of the collective. This was the case back in the 1870s, when the top hats gathered in Victoria and Ottawa to orchestrate a land giveaway of epic proportions. I’ll exploit creative license and place them all in the Bengal Room at the Empress Hotel.

Conspiratorial backslapping and hearty laughs would have been suffused in an atmosphere of ice cubes tinkling in crystal snifters, expensive cognac, and imported cigars. Like a lot of countries that are contrived out of conquered indigenous lands, the creation of Canada involved a series of horse trades. Canada was a fledgling concept in the late 19th century. As part of its commitment to connect the seaboard of B.C. with the railway system of Canada, the federal government of the day agreed to contribute $100,000 annually towards the construction of a railway on Vancouver Island. British Columbia kicked in more incentives, promising roughly 8100sq km and $750,000 to the company that constructed a railroad on the island. It’s difficult to imagine how insulting this would have been to the K’ómoks, Cowichan, Halalt, and other First Nation communities who had inhabited these lands uninterrupted for thousands of years, leaving a footprint on the landscape as subtle as an eagle feather on a sandy beach, compared to what followed under colonization. In 1884, with cash and land riches on the table, shrewd businessman Robert Dunsmuir negotiated behind the scenes with dominion officials to form the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway Company, making himself president and owner of half the shares. The Scotsman cared little about railroads. He wanted what was on and below the ground: timber and coal. This land gift, known as the E & N Land Grant, would make the Dunsmuir family one of the province’s richest. Dunsmuir’s dangerous coal mines, where non-white workers earned less than half the wage of their white counterparts, would also fuel some of the province’s most bitter labour battles as miners struggled for fair pay and safer working conditions. To add insult to injury, Dunsmuir only partially fulfilled the railway promise as the tracks stopped abruptly in Courtenay before reaching Campbell River. The family fortune fueled the construction of Craigdarroch Castle on a 28-acre estate overlooking Victoria, which was by far the most lavish private home ever built in B.C.

In the years that followed Dunsmuir’s halcyon days, his land was parceled up, then sold and resold multiple times over to various logging and resource interests. To this day, the land grant haunts Vancouver Island, shaping land use, development, and access in profound ways. With Crown land there are provisions and regulations in place under the Ministry of Forest, Lands and Natural Resource Operations to enable and encourage both public and commercial recreational access, such as the tenure system that allows heli-skiing companies to operate on public lands, or Recreation Sites and Trails B.C., which authorizes the construction of trails on Crown land. There are also provisions for watershed and riparian protection to safeguard public drinking water sources.

Conversely, on Vancouver Island’s private timberlands, it’s historically been a sort of cowboy country where we rely on grassroots public activism and the hoped-for goodwill of forest corporations headquartered in distant high rise office towers, who answer to shareholders first and communities second, to get things done on these lands.

If I had to classify myself politically, I would be a social democrat. In Texas, they would call me a communist. I’ll unpack my admittedly loosely constructed ideology. I believe that resources like water, forests, minerals, fish, and most land should be publicly owned and sustainably managed by an accountable, progressive government of elected individuals tasked with balancing ecosystem health and deriving the most public good from precious resources, all within a political culture that fosters entrepreneurial spirit, creativity, and diversity. That’s not too much to ask, is it? Does that make me a Scandinavian communist?

British Columbia is a perplexing place. We have all the tools in place to create this Scandinavian utopia. We’re blessed with abundant raw resources and more than 96 per cent of the province is Crown, or publicly owned, yet like most jurisdictions on the planet, we struggle to strike a rational balance between economy and ecology. There is something called the “tragedy of the commons” that must be acknowledged. In essence, it’s when individuals put their self-interest ahead of the public good, to the point where said resource eventually disappears. The Atlantic cod fishery, when fishermen blindly decimated a stock that seemed inexhaustible just a few generations before, is a classic example of this tragedy and the profound failure of management of a common resource. But there’s also something I would call the triumph of the commons. The dogged efforts of the Cumberland Community Forest Society to reclaim land around the village is an obvious local example. But there are many. In the Kootenays, the 11,300 hectare Harrop-Proctor Community Forest is a Crown land tenure that enables this community to manage its surrounding forest with a light footprint. A sustainable harvesting program that processes timber at a local mill generates a small stream of revenue for community projects, creates local jobs, and protects its drinking water source. That’s why the fact that B.C. is 96 percent publicly owned land (or Crown land) must be treated as a hugely valuable asset for present and future generations. Sure, it’s a work in progress. I could fill volumes about corporate excess on public lands, but the essential element remains: public ownership of the broad land base and adjacent resources of the sea.

The E & N Land Grant is a textbook lesson on how decisions made more than a century ago can affect the lives of ordinary people in perpetuity, making Vancouver Island, especially the southeast coast where we live and play, an anomaly. The clock can’t be unwound; it’s something we have to live with. And for this, we can thank the top hats who met in the Bengal Room, or some other similar establishment, to carve up the landscape and its riches more than a century ago.