Near the end of July 1918, the blackberries were just starting to ripen, a welcome development for the hungry draft evaders who were hiding in the hills behind Comox Lake. The mission to capture them had intensified now that Albert “Ginger” Goodwin was among them. The men delivering supplies up the Cruickshank were being watched by Special Constable Dan Campbell. And he was close. They had to keep moving.

In 1910, Goodwin came to the area to work at No.5 mine as a mule driver. He’d been “down the pit” in Yorkshire, England at 15 years old and in Nova Scotia at 19 before moving west with friends.

Conditions in the coalmines on Vancouver Island were brutal. Men were more than four times as likely to die on the job here than in the UK; the Dunsmuir mines were gassy and dangerous, and the anti-union sentiments of their owners were well known.

“The time for revolution is rotten ripe, but the mind of the vast majority is not ready and the struggle takes on the form of an intellectual one for the possession of the mind of the working class.”

—Goodwin in The Western Clarion, November 22 1913

A socialist, conscientious objector and pacifist, Ginger was blacklisted for his union activities during the Big Strike of 1912-1914. He moved to Trail, worked in the smelter, and continued to agitate for the cause of an eight-hour day and safe working conditions. He ran for public office, advanced in the local labour organization, and made his views about fairness and distribution of wealth well known through both speeches and writings. Goodwin was the red rose of the labour movement in British Columbia, and a thorn in the side of the Capitalists whom he believed were the only ones benefiting from the war.

When conscription was introduced in 1917, Ginger registered for the draft and was classified as unfit for service. His scrawny stature, poor teeth, bad stomach (probably an ulcer), and the beginnings of black lung were reason enough to keep him out of the trenches. But eleven days after he led a strike in Trail that shut down the smelter, he was reclassified as fit to serve. The timing of this reclassification was suspect, and the tribunal that heard his appeal was made up of men with their own interests at stake. Some called him a criminal for evading the draft, but when the system itself is structured in such a way that the workingman has no recourse, it’s hard not to feel sympathy for his situation. He wasn’t going to fight, and fled for Cumberland.

“Whether he was shot in the front or the back, he got his just and due deserts [sic]. He was an outcast, an outlaw, and not deserving of any sympathy.”

—Sgt. A.E. Lees, Vancouver Sun, August 3, 1918

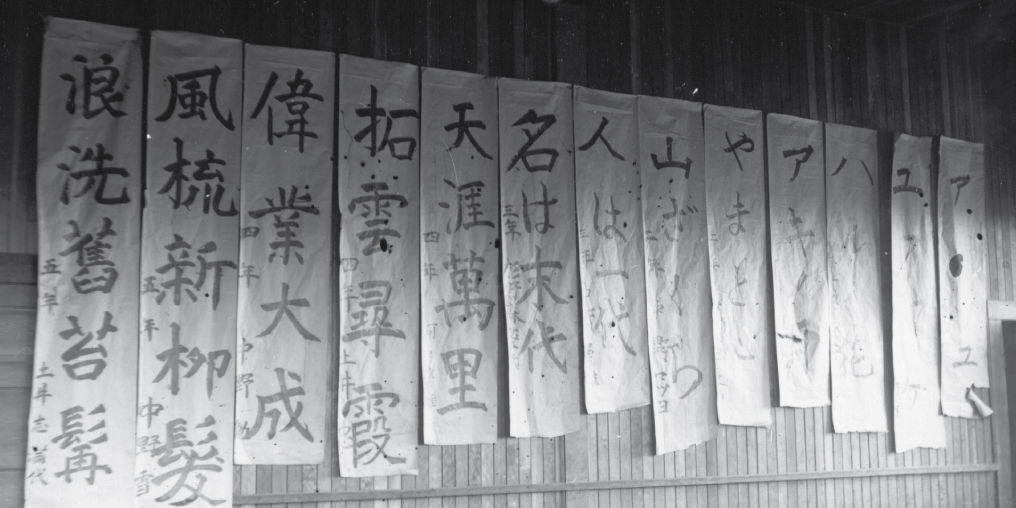

What happened behind Comox Lake on July 27, 1918 remains contentious to this day. Murdered in cold blood or shot accidentally, the result was the same: Ginger was dead. His body was brought down and laid out in the Bank’s funeral home. His white coffin was hoisted on a bier, and row upon row of miners, merchants and police among others took their turns carrying his body to the Cumberland Cemetery in a procession more than a mile long. On August 2, 1918 in Vancouver, his death sparked the first General Strike in Canada. He was and always will be “a worker’s friend.”

“He was well posted on the working class movement, an orator of no mean ability, and a gentleman in the best sense of the word; kindly-hearted, earnest and sincere in his efforts to bring about a change in the system which he knew so well was the cause of wars, and all the ills from which society suffers.”

—Union Leader William Pritchard, BC Federationist, August 2, 1918

The 2018 Miners Memorial Weekend takes place June 22-24 in Cumberland, and commemorates the 100th anniversary of the shooting of Ginger Goodwin. The Cumberland Museum and Archives pays tribute to this important historic event through participatory art and music projects, an exhibit titled “Goodwin’s Reach,” an arts symposium, workshops and talks, the re-enactment of Goodwin’s funeral procession, and other engaging programming. The goal of Miners Memorial is to bring to light the story of Albert “Ginger” Goodwin and the ongoing fight for labour rights, both historically and within a wider contemporary context. There are many ways to engage. Find out all the details at minersmemorial.ca.

PHOTO: ALBERT ‘GINGER’ GOODWIN’S FUNERAL PROCESSION. DUNSMUIR AVE, CUMBERLAND BC. AUG 2, 1918. COURTESY OF CUMBERLAND MUSEUM AND ARCHIVES C110-001.