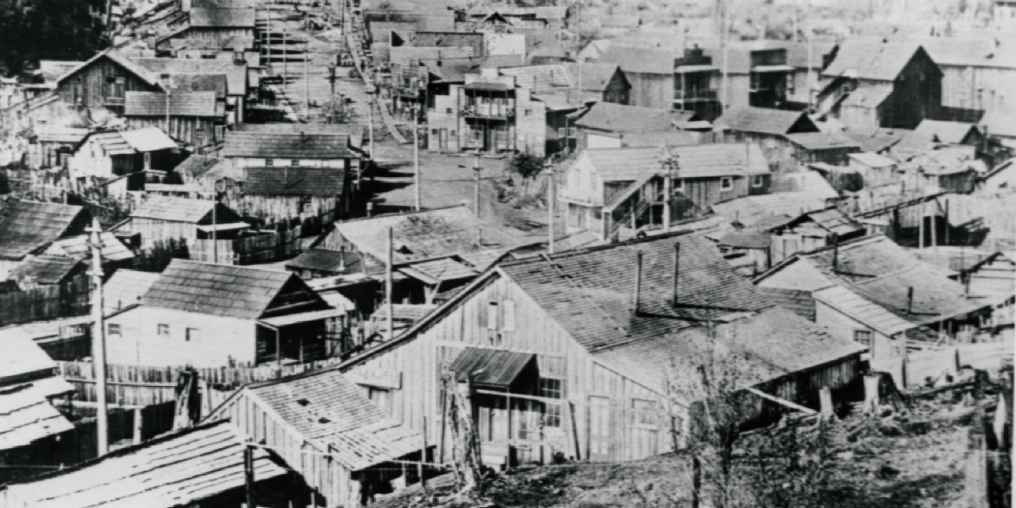

At Cumberland Chinatown’s peak in the years just after the end of World War I, around 1500 residents bustled down the wooden boardwalks between mining shifts. The Chinese miners might have dropped their coal-dust-crusted linens to a laundry before ordering gai lan or pac choi, vegetables grown and served at the Chinese restaurants. Situated outside the city limits of Cumberland, Chinatown was a self-sufficient community with its own customs, commerce, and laws.

At one time, there were 24 grocery purveyors, four restaurants, five drugstores, a temple, two 400-seat theatres for Chinese opera performances, and 18 gambling houses. Sun Yat-sen, the famous revolutionary statesman, made a stop here in 1911 as he rallied support for his ideals that would later evolve into the Republic of China.

Today, you are more likely to slap a mosquito on your arm while playing disc golf than to read the placards nestled between native plants that describe the once-robust Chinese community.

What happened to this bustling society in the swampland?

In the 19th century, Chinese began immigrating to North America, which they called Gum Shan (Gold Mountain), on the promise of a more prosperous life. In 1858, the first steamboat of Chinese miners arrived in lək̓ʷəŋən territory, now called Victoria, although Chinese labourers were recorded in fur-trade colonial settlements in Nuu-Chah-Nulth territory as early as 1788.

Unlike other nationalities, Chinese immigrants and their Canadian-born descendants were not granted rights. Thousands of Chinese workers were enticed to work on the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), but once it was completed, they were viewed as disposable. To discourage Chinese from staying, laws were created that restricted access to government contracts and business licences, and children of Chinese descent had to attend segregated schools. Provincial legislation created in 1872 prevented First Nations and Chinese people from voting.

With the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885, the federal government imposed a head tax on Chinese entering the lands now known as Canada that started at $50 and eventually increased to $500, roughly equivalent to two years’ wages for the average working Chinese.

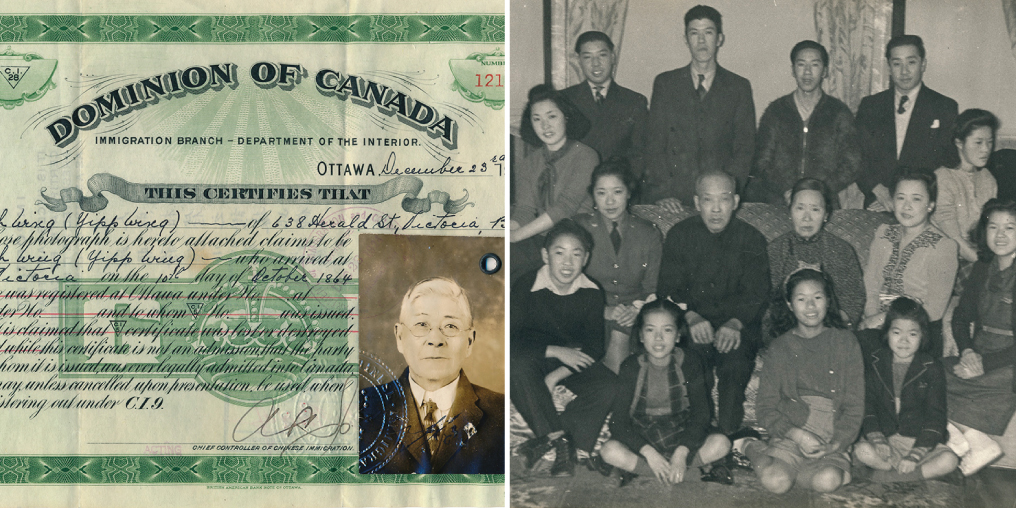

My great-great-grandfather, Ah Wing, arrived in the early phase of Chinese migration via San Francisco. His son, Jack Nam Yipp, was among the first generation of Chinese born in British Columbia in 1899. Jack was given a Chinese Immigration (C.I.) certificate. These certificates were used to enforce surveillance of Chinese movement in and out of the colony. When Jack later wanted to study in New York, he needed further documentation from the government to grant travel.

Though Ah Wing kept his family in Victoria’s Chinatown, where he eventually became a police interpreter, many other Chinese travelled for work under mining contracts.

In 1888, around 200 Chinese were hired (at half the wage of white labourers) to open the first Cumberland mines and to build the railroad for shipping coal to Union Bay. Often, the Dunsmuir family’s colliery companies paid the head tax and passage fare from China; repayments were deducted from the miner’s wages.

Chinese worked the most dangerous jobs on the CPR and in gold and coal mines. They also fought in World War I. Nevertheless, in the early decades of the twentieth century, anti-Asian sentiment gained momentum in British Columbia. A branch of the Anti-Asiatic League (AAL) was formed in Cumberland in 1921.

With pressure from the Comox-Alberni Member of Parliament, Alan Webster Neill—a former Indian agent who was an advocate of residential schools and a member of the AAL—the federal government passed a new Chinese Immigration Act (more commonly known as the Chinese Exclusion Act) on July 1, 1923. The Chinese community called it Humiliation Day.

The Exclusion Act prohibited all Chinese immigration into Canada, with very few exceptions. It created a class and gender divide: only those who had been wealthy enough pre-exclusion to bring their wives over from China were able to have families. Labourers who had been paying off their steamship passage, or saving up to bring their families over, were now trapped as lonely sojourners. For over two decades, boarding houses in Canadian Chinatowns rarely heard the cry of a baby because of this legislative racial discrimination.

My great-uncle, Billy Keen, served in World War II on an all-Chinese-Canadian paratrooper squad. Despite having risked his life for Canada’s war effort, Uncle Billy, like all Chinese Canadians, was not allowed to vote. It took a long period of advocacy before Chinese Canadian veterans got the vote back in 1945, two years before the rest of the Chinese in Canada did.

After 24 lonely years, the Exclusion Act finally ended in 1947. But its repeal came too late to save the Cumberland Chinatown. A fire in 1935 engulfed one third of the settlement. Many residents had already left for larger cities because mining jobs had dwindled after oppressive laws, implemented in 1923, banned Chinese miners from working underground.

Some families stayed in the Comox Valley and opened businesses, including Leung’s Groceries and Rent-All Equipment in Courtenay, which is still run by descendants of the Leung family. COOKS Restaurant in Cumberland now operates out of the original location of Leung’s Groceries.

An attempt by the Cumberland Chamber of Commerce to revive Chinatown as a tourist attraction was unsuccessful in 1963—provincial funding was instead awarded to Barkerville. The remaining structures were burned by the Cumberland Volunteer Fire Department after the village site was deemed a safety hazard.

The next time you wander down to the disc golf course, imagine the dramatic face paint of a Cantonese opera singer, the clicking of mah-jong tiles on a gambling table, or the clanging of the mining shift bell. Once, Cumberland Chinatown had a pulse.

The exhibit currently on at the Cumberland Museum, A Seat at The Table: Chinese Immigration and British Columbia, highlights the complexities resulting from the systemic discrimination and abundant racism towards Chinese communities province-wide. It has taken generations of activists and resilient Chinese Canadians to earn a seat at the table. The exhibit honours the stories of those generations who advocated for our rights, so that I can be here today, writing this article.