In October 2023, I had the chance to speak with Wedlidi Speck. Wedlidi is Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-cha-nulth, and E’iksan, and is the head chief of the Gixsam namima of the Kwaguł tribe. As a spiritual leader, he has had an interest in cross-cultural communication for nearly 35 years. While the word limit has precluded the chance to share our entire conversation, I hope you enjoy this snippet. If you are interested in learning more about Wedlidi, check out his three episodes on this podcast.

Dave:

Can you introduce yourself?

Wedlidi:

I was born and raised in Alert Bay and moved to the Comox Valley about 35 years ago. My grandmother, Nellie, was part of one of the three tribes of the Comox Valley. Her tribe was the E’iksan. That means people of the sun. And our crest is the sun—so, fire in a different form.

Dave:

What is your role with fire?

Wedlidi:

You know, it’s interesting. There are different roles that I play with fire. I started off about 40 years ago as a fire keeper for a spiritual ceremony called a spirit lodge, often referred to as a sweat lodge, and that requires doing ceremonial preparation for lava rocks, and the wood you put in, the prayers that you do. You are constantly adding to the wood to generate the heat, so you get to know fire.

Before that, when I was really young and being mentored to be a chief, one of my roles was to tend to the fire in our traditional big houses, and that was to help me understand the symbolism of the fire because in our culture, the ceremonial house is actually considered to be the ancestor.

Let’s say you came from a whale clan; the house is actually a whale. The doorway is the mouth of the ancestor. The rafters are the ribs, and the beam is the backbone. The fire at the centre of the house is called the soul of the house—the soul of the ancestor. By preparing the fire a special way, we can communicate with the ancestors in a really good way.

The fire is considered to be male and female. One part of the fire provides illumination, direction, and clarity. And the other part of the fire provides warmth, a sense of security. My old mentor—his name was Chief James Sewid—said to me one day when we were in the big house, “Look at that fire. Remember, your leadership will be like that. You will be a leader who will provide illumination, direction, and a sense of safety, or you’ll be a leader who burns and destroys and leaves people feeling isolated. That’s always your choice in leadership.”

That’s a backdrop to a kind of philosophy to fire.

My father told me a story about his grandmother, my great-grandmother. Her name was Mary Hanuse. Mary would take the grandchildren in her canoe, She would go around an island and she would pray, and at a certain point, she would set fire to the island.

The first time he saw this, my father, being young, thought she was going wacko, but she eventually told the kids what she was doing, saying she was preparing the ground for the berries that will come, so they will be healthy.

That was an early exposure for him to what fire meant to our people. That happened in the summertime. The reason I know that is because the grandkids would have been in the residential school during the spring, fall, and winter.

Dave:

What does that story mean to you?

Wedlidi:

My great-grandmother was quite an amazing woman; her name was Kumanux, which translates to “wealthy woman.” When I think about the burning of the island, [I realize she had] a deep understanding of husbandry that she would have learned from her mother. That mentorship was really significant to understanding the plant world, understanding food, understanding harvesting, and so forth.

There’s a term in our language, ta-ka: it means “good land.” Ta-ka is about making sure that you’re looking after the land and supporting it. They wanted good food and good ground; fire played a really important role in that. They had a deep understanding about what fire does to some seeds.

I get the sense that we’re not separate from the land. We’re part of it, and it’s part of us. It speaks to some of our language. There’s a term we have in our culture, awitnakula. It means to be one with heaven, the air, land, the sea, and everything in it.

It points us in a direction of being in good relationship with all the things that are seen and unseen. Knowing that, our behaviour is a conditional factor here. That if we’re not in good standing, the resources around us will respond in kind.

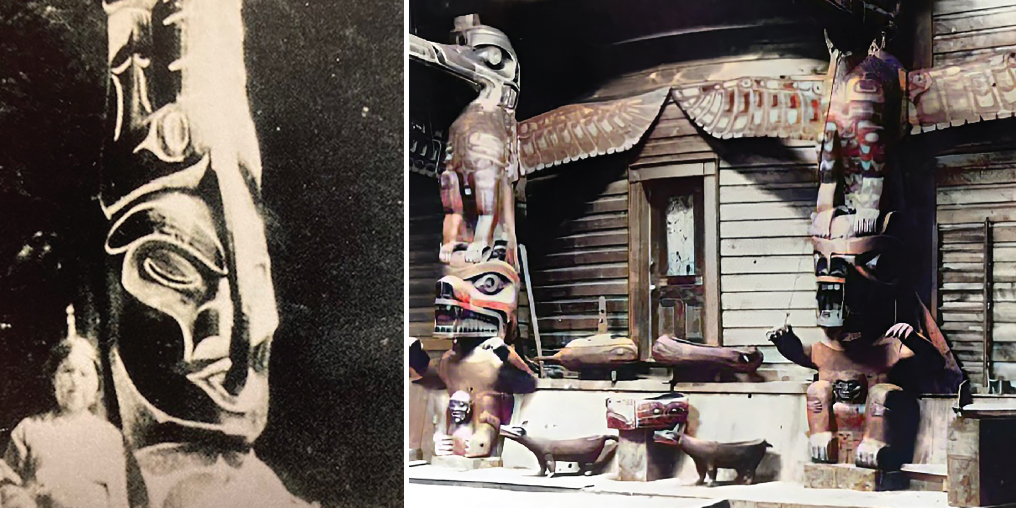

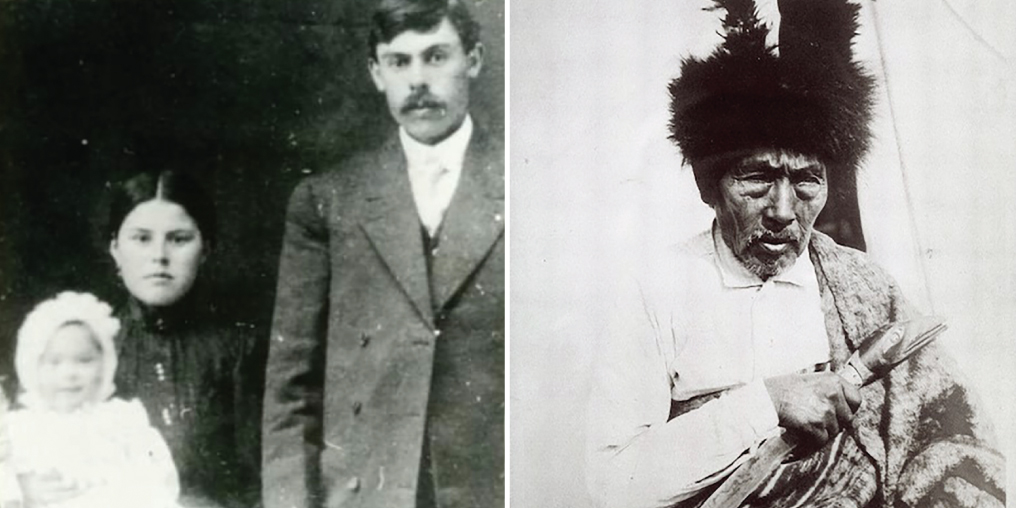

ABOVE LEFT: MARY HANUSE, HUSBAND HARRY, AND DAUGHTER ANNIE. ABOVE RIGHT: MARY’S FATHER, CHIEF XALLXID. FEATURED PHOTO LEFT: MARY HANUSE, WEDLIDI’S GREAT-GRANDMOTHER, STANDING BESIDE HER LATE HUSBAND’S MEMORIAL TOTEM. FEATURED PHOTO RIGHT: INTERIOR OF HANUSE HOME.