Most Campbell Riverites know the iconic blue cottage, nestled by the beach in Willow Point. For Sybil and Walter Andrews, it was home. For many, it’s a visual marker reminding us of where we are. For some, it’s a historical landmark, harkening back to a time when our people were known for their toughness and our region was a frontier, capturing the imaginations of those seeking true wilderness. And for a select few, it’s the place they found their artistic voice under the guidance of a true force.

Sybil Andrews (1898-1992) made a significant impact by forging into areas where the female experience was largely absent. She engaged in firsts for women as an industrial labourer, and as an artist. She exhibited incredible work ethic and grit throughout her time as a welder for the World War I and World War II efforts in England; as an art student pursuing further learning at night while teaching by day; by persevering to attain excellence in a male dominated and exclusionary field; and as an adventure seeker who moved with Walter Morgan to the isolated Canadian logging community of Campbell River in 1947. The exhibition Finding Sybil: Contemporary Responses to Sybil Andrews, on from March 6 to May 1, 2021 at the Campbell River Art Gallery, acknowledges the enduring legacy of this influential and groundbreaking artist by presenting a dialogue on the impacts she continues to have through the lens of contemporary, working artists.

Sybil Andrews took up the linocut as a result of her work and tutelage at the Grosvenor School of Art. Printmaking is among the most democtratic art forms. It is widely respected by artists for its accessibility, opportunities for experimentation, and its ability to reach a broad and disparate public. Travelling widely and traversing national boundaries, prints have played a pivotal role in disseminating information on political movements, cultures, art movements, alternative viewpoints and propaganda.

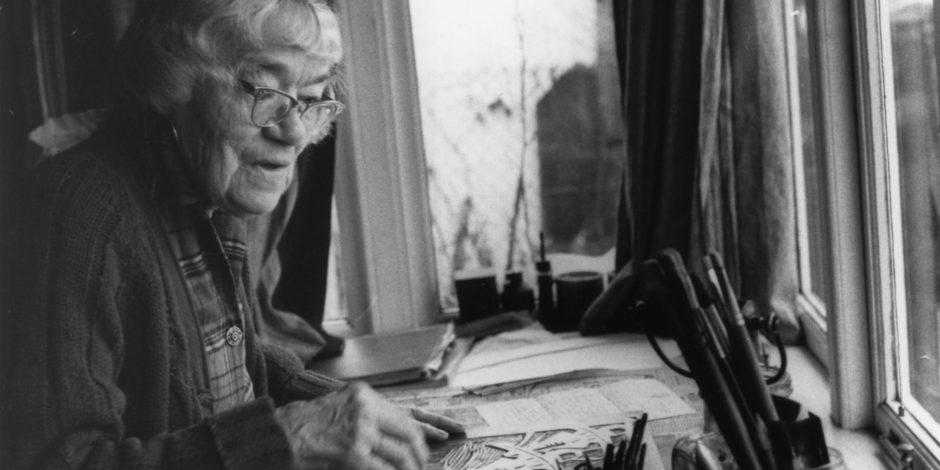

Although Sybil’s main medium was the linocut, she worked and taught in a variety of media. She was an accomplished draftswoman, watercolour artist, etcher, and textile worker who taught observation and technical skill through sketching and painting. She applied a rigorous attitude in her teaching to instill in her students the values of investing themselves into their art and infusing each work with the energy of life by dispensing with unnecessary detail and getting to the heart of their subject.

Andrews’ respect for diverse artistic voices stands out in her manifesto Artist’s Kitchen: “Cultivate tolerance and an open mind, instead of condemning that which you do not like or understand. Instead, find out what it was the artist was endeavouring to express. Then go further and ask yourself why you don’t like it or why you do. You will develop your entire faculty and grow to appreciate and delight in all forms of art: Perhaps even those that, at one time, you could not abide!”

In curating Finding Sybil: Contemporary Responses to Sybil Andrews, we invited a range of voices that illuminate important aspects of Sybil Andrew’s creative life, including a blacksmith and sculptor to accentuate the movement and depth of Sybil’s work, as well as draw relationships across mediums. The exhibition also features Queer perspectives to ruminate on the spiritual and technical aspects of Sybil’s oeuvre. To paraphrase Sybil, the spiritual quality of art lies in the emotions and thoughts experienced in the artist’s mind and communicated through an artwork. The linocut is a medium that forces the artist to focus solely on ideas through the necessity of simplification.

A local textile artist will highlight important elements central to our understanding of Sybil’s work ethic and artistic process. Quilting mirrors aspects of labour, planning, layering, and feminist practice in Sybil’s work, not to mention her artistic talent in embroidery.

The vision and voices that knew and worked with Sybil will carry through the work of her students shown in this exhibition. Her role as educator is central to how many remember her, and the teachings and strong tea shared in that blue cottage resonate in our community to this day.

Finally, it was important that Indigenous voices resonate through the exhibition. Sybil respected First Nations cultures; she found them to be very sophisticated, and admired their carving abilities. Andrews made work in response to Indigenous ceremonies that she witnessed. In her linocut Indian Dance, 1951 there is a striking depiction of faces in the figures, which she rarely portrays in her human subjects. A fusion of regalia, mask, and movement accentuates the spiritual energy and unity of the dancers. As such, the exhibition holds space for contemporary Indigenous artists to respond to her legacy as active voices.

Inviting artists to respond to the life, art, and philosophy of Sybil Andrews was such an enriching exercise. For the artists, it was an inspiring window into the processes of a great mind. Our hope is for visitors to experience her work in a new way, illuminating the enduring power of her legacy.

The tenacious spirit, vision, and attitudes that shine through Sybil Andrews’ written and visual work are still relatable and have much to teach us. Her images continue to grab our imaginations and sweep us up in the energy of their movement and power. Artist’s Kitchen resonates with her boldness and belief in the power of art: “Great Art isn’t effect. It is something which teaches and reaches the vitals. The response is of the Spirit and endures. The Artist has something to say which cannot be hidden.”