It’s a crisp November morning and the autumn sun has just breached the Beaufort mountains, casting gold and pink shadows through the bare-limbed forest. As I arrive at the riverbank, I’m greeted only by the sounds of splashing chum salmon in their upriver battle to spawn. On instinct, I scan the opposite shore for a black bear family, the only other locals to visit this remote reach of the river.

I’ve been coming to these rivers for months now. While my purpose here is to conduct scientific research, the hours that I spend on these riverbanks allow for deeper reflection. I begin to realize that underneath the deceivingly calm surface, the rivers take on a contrasting balance between supporting life and casting death; they are nature’s perfect juxtaposition. As the spawning season progresses, this theme becomes more prevalent, both with the wildlife I am studying and in my personal experiences.

Physical discomfort after hours in the wind and rain is a contrast to the inner calm I find while isolating myself from town. On the river, I am constantly alone but simultaneously in the company of others, though many have more legs than I do. The rivers seem to transition from an objective laboratory to a sort of temple; instead of focusing on counting fish and taking observations, I begin to notice the sound of gurgling water calming my mind. These daily waves of altering joy, discomfort, and revelation make me acknowledge that rivers are even more dynamic than they seem.

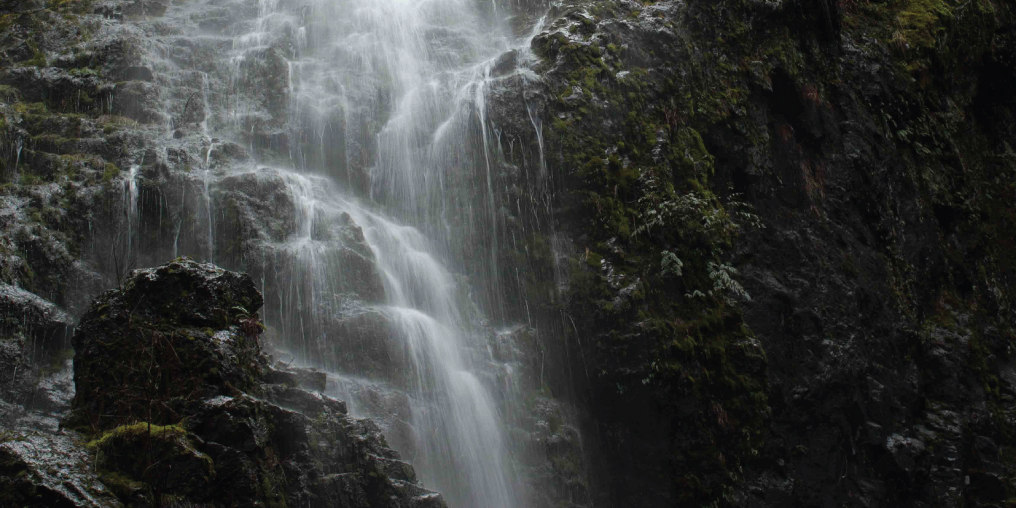

Rivers have tremendous power to shape the physical land. They carve canyons through mountainsides on their path towards the sea, while simultaneously acting as arteries to the landscape by moving the ecological currency of our coastal habitats upriver. Anadromous, meaning born in freshwater and returning to their natal rivers to spawn, describes pacific salmon species, which are the energy-rich sustenance that move up our rivers every fall.

While witnessing thousands of salmon fighting their way up river is a wonder to behold, the real magic happens when predators from tiny to mighty begin to drag and fly their carcasses into the forest. Bald eagles, the kings of the sky, are a primary transporter in moving salmon nutrients inland. Eagles will congregate on riverbanks to forage, which often results in individuals fighting over salmon carcasses. The winner will fly their bounty to a nearby tree where they consume the salmon tissue. The remaining bones and cartilage are unceremoniously dropped to the ground and continue to decompose. The nutrients that accumulate in salmon during their adult life stage at sea are then absorbed into surrounding vegetation and cycled through the forest food web. These nutrients help everything from insects to cedars grow and thrive. With modern science, we can trace this cross-ecosystem nutrient cycle, which begins in the sea and ends in the land, all because of spawning salmon and the rivers that carry them.

While it’s easy to be enamoured by the salmon life cycle and the predators that transform their death into life, days and months spent on riverbanks deepens your respect for the rivers. You quickly realize that it’s the rivers that dictate the constant exchange between life and death. While juvenile salmon spend their first couple of years in the nursery of shallow, dammed pools, their older comrades struggle to move up river through the obstacles. The fall rains bring the water necessary for adults to spawn, while also washing away sediment, gravel, and the eggs that are the promise of more salmon.

Spending time on rivers, you begin to understand that they are multidirectional. They are a mover of the physical out to sea and, simultaneously, a conduit for sustenance inland. They are life-giving and death-bringing; the lifeblood to our land and a shaper of our Valley. And for the visitor, they can be both peaceful and threatening, but their ability to nourish the land and calm our minds is always inspiring.