One of nature’s fundamentals is the way matter flows in loops, supporting life as it transforms from one state to another. Without the cycling and recycling of carbon, oxygen, nutrients, and water, our life support systems would grind to a halt.

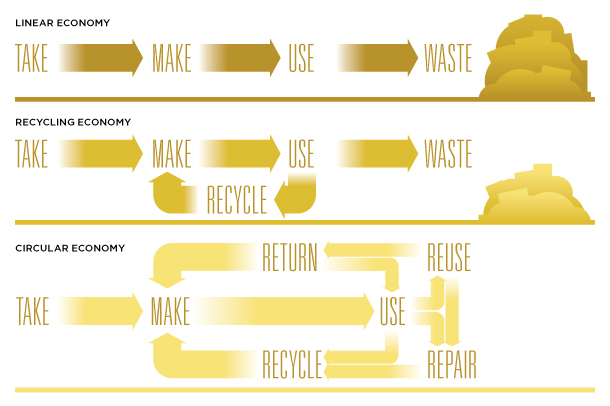

By contrast, modern human economies flow in straight lines. With the help of fossil fuels, most human systems begin with resource extraction and end in a landfill, or with waste fouling the air, land, and/or water.

Carbon dioxide is the most obvious example. Plastics are another. One high-profile study predicted that by 2050, there would be more plastic in the sea than fish. While details of the study are disputed, no-one disputes the global plastic-waste crisis.

Is better recycling the answer? Right now, less than 11% of plastic waste is recycled in Canada —even lower than the global estimate of 14%. Better recycling would be a start, but the global tsunami of plastic waste can only be properly dealt with at the source.

How can we move away from the take-make-waste extractive industrial model and towards circular economies that support life on our planet? What does a circular human economy even look like?

SYSTEM CHANGE

In a circular economy, waste is designed out of the system. Resources are kept in use as long as possible through re-use and repair, until their components are recycled to feed the system again. This contrasts with the prevailing paradigm of planned obsolescence, where things are built to break and where products are designed so they cannot be repaired.

Circularity requires a total re-think of how and why things are made and sold. System-level intervention is needed. While consumer activism is essential, our governments also need to step up. Fortunately, in the case of plastic, Canada has joined other countries in trying to address plastic waste at the source.

In 2018, our Courtenay-Alberni MP Gord Johns proposed creating a national strategy to clean up and put an end to plastic pollution. His motion passed unanimously in the House of Commons, leading to an official vision of keeping all plastics circulating in the economy and out of the environment. While the detailed plans will take time, the federal government will ban some forms of single-use plastic beginning in 2021. Meanwhile, consumer petitions are targeting Canada’s major grocery chains, challenging them to reduce their packaging and ban plastic bags. And the zero-waste movement is taking off worldwide.

Zero-waste is both a philosophy and a lifestyle focused on eliminating waste completely. “Zero-wasters” fight back against consumer culture by buying less and re-using more of everything. Refusing or minimizing wasteful packaging is a big part of the practice.

Creating zero waste as a consumer is nearly impossible in rich countries today. Yet support for zero-waste living is taking off. In the Comox Valley, a new zero-waste Facebook group gained 1,000 members in six months, becoming a major source of local advice. Enthusiastic participants are sharing all kinds of reducing and reusing tips on this forum—from which restaurants don’t mind Tupperware takeout containers, to whether using a bidet really works, to which store sells the good kind of silicone zip-top bags. These plastic-averse, pro-organic consumers shop at zero-waste-aware retailers like Edible Island and Seeds, grow their own food or buy from local farmers and growers, and are regulars at the Comox Valley Farmers’ Market.

Another exciting development is the launch of the Local Refillery, a zero-waste grocery store in downtown Courtenay. While founder Ginette Matthews acknowledges that selling zero-waste goods seems contradictory, she is a passionate promoter of the circular economy. For her, it’s about being part of a movement. “Every time I have a conversation with a supplier about finding a new way of packaging and selling their product, I am educating them about the consumer demand for zero-waste solutions,” she says.

She spent months building her supply chain and encountered all the typical reasons for overpackaging today: food-safety standards, a reluctance to part with carefully branded packaging, manufacturing constraints, and resistance to the cost of making changes. But finding suppliers willing to take the risk affirmed Matthews’ reasons for opening her store: to raise awareness and create daily positive change.

As the influential zero-waste blogger Anne-Marie Bonneau says, “we don’t need a handful of people doing zero waste perfectly. We need millions of people doing it imperfectly.”

To which we could add: “And we need to demand action by government and businesses to reduce packaging and incentivize stewardship of all our resources—plastic included.”

There is a pressing need to relate to our home planet in a more thoughtful way. Dealing with the disastrous results of today’s linear economies is a massive task. We’d best get started, because the other option is a dead end.